John McCleary died at the age of 83. He lived a nice long life, you might say. Maybe, but John’s life was still unexpectedly cut short. Not by an accident or a heart attack or cancer. By an infection. That he picked up as a patient in the hospital.

A few years back, John fell and broke his fibula, the small bone in the lower leg. He was hospitalized for 12 days for treatment and rehab. When he returned home, he needed to use a walker but other than that he seemed fine.

The next day was a different story, says his daughter Kathy, who is a nurse.

His second morning home he woke up so sick and weak he couldn’t sit up in bed. My mother was scared to death. We discovered he had a high fever. He ended up going back to the hospital and long story short, he had contracted MRSA pneumonia during his rehabilitation.

Kathy Day, RN, John’s daughter

What is MRSA?

MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) is a strain of staph infection that is resistant to antibiotics normally used for staph infections. One-third of us carry staph bacteria in our noses. Most of the time, we don’t get sick. Two in 100 people carry the MRSA strain.

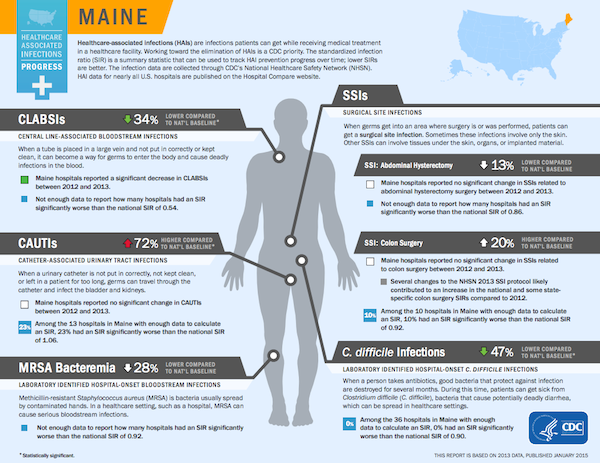

Although you can get infected out in the community, most MRSA infections happen in the hospital or some other healthcare facility. It’s a huge issue, but MRSA isn’t the only worrisome hospital-acquired infection. This screenshot from the CDC website shows several hospital-acquired infections that are seen in Maine.

When John McCleary was first diagnosed with pneumonia, he was given regular antibiotics — the kinds that target a wide spectrum of bacteria.

The day after he landed back in the hospital, he showed signs of sepsis, which is a serious, sometimes life-threatening reaction to an infection.

When infection leads to sepsis

Here are some of the symptoms of sepsis courtesy of the Mayo Clinic:

Sepsis

To be diagnosed with sepsis, you must exhibit at least two of the following symptoms:

- Body temperature above 101 F (38.3 C) or below 96.8 F (36 C)

- Heart rate higher than 90 beats a minute

- Respiratory rate higher than 20 breaths a minute

- Probable or confirmed infection

Severe sepsis

Your diagnosis will be upgraded to severe sepsis if you also exhibit at least one of the following signs and symptoms, which indicate an organ may be failing:

- Significantly decreased urine output

- Abrupt change in mental status

- Decrease in platelet count

- Difficulty breathing

- Abnormal heart pumping function

- Abdominal pain

Kathy’s father became so ill that among other things, he had to be catheterized. Soon after, MRSA showed up in his urine.

When he developed MRSA in his urine, I said wouldn’t it be a good idea to culture his sputum? That’s when they diagnosed the MRSA in his lungs and they changed him over to a different antibiotic. It was about six days in from the day of his admission.

Kathy Day

Kathy says they later found out that the same month her father was admitted for his broken leg, two patients had died of MRSA infections after joint replacement surgery. In her opinion that constituted an outbreak.

Basically, they were having a small outbreak, and none of my family was given any education on infection control or any information or warning that they had this problem. Nothing. So we weren’t looking for any signs of infection practices at the hospital or paying much attention to that.

Kathy Day

The MRSA infection blindsided John’s family, especially Kathy.

I suspect, but I’ll never know, that he contracted it possibly from a roommate or he was in a room that was contaminated and never cleaned thoroughly enough. It had to have happened from one of those two things.

Kathy Day

She had always tried to be a strong patient advocate, but after what happened to her father, patient safety and preventing medical errors became Kathy’s passion.

In 2009, she authored a MRSA prevention bill.

It was quite extensive. One part of the bill passed into law, requiring screening of all high-risk patients for MRSA upon hospital admission. I wrote an addition to the law that would expand it and include more high-risk patients. Rather than expanding it, the Maine Hospital Association wrote an opposing bill to rescind the existing bill, which passed. It had only been a law for less than two years.

Kathy Day

Rather than let herself be defeated as well, Kathy continues to be a strong and outspoken advocate and also maintains an active blog called McCleary MRSA Prevention.

The effects of medical errors

An estimated 440,000 Americans die each year because of medical errors. Some consider it the third leading cause of death after heart disease and cancer.

The International Journal of Healthcare Improvement published the results of a survey conducted from 2010 to 2013 by the patient advocacy group Empowered Patient Coalition. The voluntary online survey invited individuals to describe how an adverse medical event had affected them and/or their families. 696 people participated.

What causes medical harm?

The survey showed (as other surveys have) that in most cases, people had been harmed because of errors in their diagnosis or treatment. Infections like the one Kathy’s father experienced were number three on the list.

- Errors in diagnosis or treatment

- Complications during surgery or a procedure

- Hospital-associated infections

- Medication errors

The survey also revealed several issues that participants believed led to the errors they experienced, including

- A lack of accountability by the provider and/or the health care system

- Deficient and disrespectful communication

- Providers failed to listen

In a press release about the study, Dr. Julia Hallisy, senior author and founder of the Empowered Patient Coalition, said, “The public is a valuable resource for adverse event reporting and should be a driving force for improvement efforts. We believe that patient-led surveys will reinforce patient trust that reporting events will effect meaningful improvements in the system and also amplify the voice of the patient in all quality and safety efforts.”

Kathy couldn’t agree more that patients need to be more involved in their own healthcare and in helping to make improvements in the system.

This is really important. I don’t think patient engagement is an option. We need to engage in our own care and advocate for ourselves because nobody else is going to do it for us like we would.

Kathy Day

She offers these tips as a start:

- Know your medical history and what medicine you’re taking.

- Be prepared for your medical appointment. These days visits are usually short. Narrow down questions to the ones most important to you when you’re in your doctor’s office.

- Speak up. “For instance,” says Kathy, “if we don’t think someone taking care of us has clean hands, we have to say something.”

- Speaking of clean hands, ask for clean hands all around — doctors, nurses, other caregivers, and your visitors if you’re in the hospital. Keep hand sanitizer at your bedside. “You can also keep Clorox wipes nearby and ask your advocates (you should not be thinking about this yourself) to keep your frequently touched surfaces clean with the wipes.”

- Whenever possible, bring an advocate to medical appointments. “It doesn’t have to be a professional advocate but a loved one, spouse, child — whoever you trust and love you know will be there for you. We need extra eyes and ears at a stressful time.”

- If your health care provider suggests a new medicine, test, or procedure, always ask these five questions from the Choosing Wisely Campaign.

- Do I really need this test or procedure?

- What are the risks?

- Are their simpler, safer options?

- What happens if I don’t do anything?

- How much does it cost?

- Never sign anything until you’ve read it or if you’ve been medicated or sedated — especially consent forms (which Kathy says you can amend, by the way.)

- Have a living will, advance directive, and medical power of attorney. “End of life can be torture or it can be gentle and peaceful and you get to choose.”

- If you’re in the hospital, get the contact information for your doctor or surgeon and the manager of the floor you’re on. “Ask until you get them. Put the numbers right in your cell phone or give them to your advocate.”

- Check a doctor’s or hospital’s rating on one of several ranking sites, such as Hospital Compare, Physician Compare, Healthgrades, and the Leapfrog Group. “It also doesn’t hurt to ask your primary care physician who they would use,” recommends Kathy. “You need to ask physicians you’re considering how many times they’re treated your condition or done your surgical procedure and what their safety records are. If you’re having surgery, sometimes you can get information from a hospital patient safety officer or infection control department about the risk of infections for your particular problem and procedure.”

You should expect a good outcome

Sadly, Kathy’s father’s story did not have a happy ending. John McCleary never fully recovered from the MRSA infection. After 21 days in the hospital, he went into a nursing home where nine weeks later, he passed away.

When he was first admitted for his broken leg, he and his family, including Kathy, expected a good outcome. She believes we should all expect a good outcome whether we are in the doctor’s office or the hospital. The reality is that our healthcare system is not perfect nor are the people who work in it. And while we may have that expectation, it’s important to be an active participant, and learn what we can do to be safe.

As Kathy says, we all need to speak up and be our own best advocates.

The advice in this story is very important. But patients and family members should be aware that this advice may create a adversarial relationship with the providers. Providers don’t like their advice to be challenged. My late husband was hospitalized with a possible cardiac issue just days before he was scheduled to begin chemotherapy for Stage 4 Multiple Myeloma. The chemo was critical to his survival….he was weeks away from certain death without it. The hospitalist scheduled him for multiple cardiac procedures that would take weeks to complete. On a Saturday, we told the hospitalist we had to leave by Monday morning to take him to chemo. We had to sign him out AMA because the doctors were livid that we did not want to follow their plan. So be prepared…the advice will not be well accepted by the medical community.