Lucille Meltz has a lifetime of experience that includes being a counselor and a life coach. She has taken classes on grief and led groups on the topic. Yet, none of it prepared her for the grief she has experienced since her husband Marty died March 18, 2015.

I knew he was going to die because he went through a long physical decline and I had lost other people who were dear to me. I think I had this little message in my head that I should know how to do this. I did in a way, but I felt like it wasn’t enough. I was always grappling with I’m not doing it right, there’s something wrong with me. I thought I was going crazy. I lost my center. I didn’t understand who I was.

When Marty died, Lucille was suddenly thrust into the world of an elder widow. She was 70 years old and while still living a full and productive life, felt very much alone. It’s an emotion that anyone who has suffered a loss would feel, but Lucille believes that when you’re older, grief can be compounded by other losses you’ve already experienced.

There are so many levels of loss and losing a life partner exacerbates all of that. Every grief you go through, you are actually grieving other losses, especially ones that you have not addressed. When you’re older, you’ve already lost so many people, places, things, experiences, your sense of self, and then you lose the major support system of your life.

She’s grateful for all the love and support from family and friends but thinks that in general, the world turns a blind eye on the elder widow. It “devalues the pain of

It’s a different kind of journey. It’s not a better journey or a worse journey but it is unique. There’s a whole lot of information that people don’t realize. It made me think, okay, I’m not crazy. It’s really, really hard. This is really an unusual situation with women who are over 65.

About two years after Marty’s death, Lucille decided to write a book about her grief journey — The Elder Widow’s Walk: A Personal Inner Journey and Guide for Bereaved Widows 65 and Beyond.

I wrote the book about grief and about the plight of the elder widow because there’s a lot of silence about it. I wanted to write something that would offer some comfort and understanding and reassurance and inspiration and affirm that you’re not crazy. I’ve talked to other women who’ve read the book and they say ‘you got it’.

Lucille’s book may be meant for elder widows, but some of her experiences are universal. Encountering people who don’t know what to say, for instance.

We don’t know how to comfort. We don’t know what to do. We feel lost. We feel embarrassed. We fear that we’ll make it worse. I can’t tell you how many people have said to me, I didn’t want to bring it up because I thought it would upset you. My answer is I’ve been upset because my husband died. There’s nothing you can say that’s going to make it worse. You’re going to help because you’re recognizing what I’m going through.

Lucille’s advice is to give someone who is grieving room to talk about how they’re feeling, about their loss, about their loved one. For instance, on the day we did our interview, Lucille mentioned that it was her 50th wedding anniversary. Marty might be gone, but there is still cause for celebration.

It doesn’t matter whether he’s here or not, it’s still my anniversary. We need to give other people who are going through a devastating loss the opportunity to remember that person because not remembering is another loss. Marty will never be dead to me, he’ll always be a part of who I am, part of my life, my experience, my history, everything.

John Tewhey welcomes the opportunity to talk about his wife Gloria, who died September 29, 2017. Some people would rather talk about anything but or nothing at all.

I belong to several organizations and go to meetings. Some people I used to be very friendly with make sure not to engage me. They don’t know what to say. Just say I’m sorry. I’m happy to talk about Gloria. I love talking about Gloria.

A lot of people don’t want to talk about death even when they’re there, when they are facing it themselves. I firmly believe that you can talk about it and that we should talk about it because pretending that death doesn’t exist doesn’t do you any favors whatsoever. I think it’s the ultimate denial.

After Gloria died, John joined a bereavement support group.

I’ve been strongly attracted to people who have lost a mate. It’s so easy to talk to them because they’ve been through the same thing. The bereavement class I was in was supposed to be five weeks and it went to eight because people didn’t want to leave. It was eight people who had lost their partner to cancer in the last year, so we had something very much in common. It was very comfortable talking with all of those people.

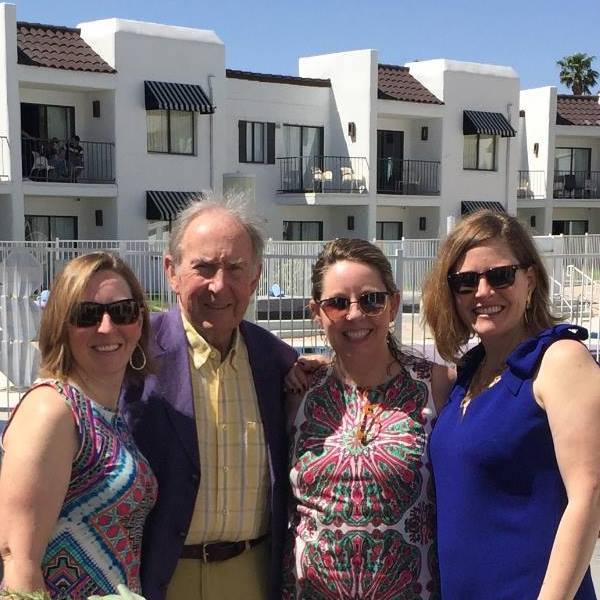

John considers himself lucky because he can also talk about Gloria with his three daughters. His daughter Kathryn said they talk about her all the time.

Sometimes members of the same family, who are also grieving, can’t talk about it to each other. Sons and daughters, for instance, may be afraid to bring it up to a parent because they’re afraid it might hurt too much. Carole Schoneberg sees it all the time. She’s an end-of-life educator and the bereavement services manager at Hospice of Southern Maine

The majority of my clients have adult children and the classic thing is the surviving parent doesn’t talk about mom and the surviving adult children don’t talk about mom because they’re all trying to protect each other. They think they’re doing the right thing and they’re afraid that if they say, oh, man, I miss Mom or Dad, it will start the crying. It will make the surviving parent cry. There’s such a lack of education and, to me, it’s also part of the power of belonging to a support group.

The bereavement support group helped John and counseling helped his daughter Kathryn (in the middle), but she says coming to terms with her mother’s death is still hard for her.

My kids are grown and I’ve been living alone and sometimes I would just sit there alone with it, so it was good to go and talk about it. My kids are a source of comfort because they loved her too and people always try to be nice .

When someone says she’s always with you I say thank you, that’s nice but she’s not. What I’ve realized recently is she really is. She is the things I do, the things I say, the clothes I wear. The attitudes I have are her and I recognize those more than I ever did.

When Jan Willis died on February 5, 2017, her grandson Will was barely a toddler. Will’s mother Jen says letters to him from friends have helped her enormously.

During the service, my father asked friends and family members to write letters to my son, Will, describing his grandmother and capturing any stories or memories they wanted to share with him to help him know her as he grew. These letters started arriving within days and folks are still sending them. They have been difficult to read at times but, while I know they are written to Will, each letter has been an incredibly meaningful part of my own grieving process.I have also found myself incorporating more of my mom’s habits like sending birthday cards, cooking some of her favorite recipes, listening to music that brought her joy, and trying to read more (which was a true passion for my mom). I feel a connection to her during these times and it brings me some peace to feel that.

Jackie Conn sees reminders of her husband Tim everywhere, even in the laundry room where his clean t-shirts are still rolled up on the shelf. He died of a massive stroke on February 18, 2018. On some level, it still doesn’t seem real to her. “Accepting that he’s gone still hurts,” she told me, “but it’s a better kind of hurt than it was before.”

When people tell her they don’t know what to say or realize that anything they say may not help her, she says she gets it.

To me, that comes across as empathetic. You understand how it feels and that it’s not your job to try to make me feel better. Some people stay away. I’ll think maybe they don’t care and then I realize I kind of make people uncomfortable. They don’t know what to say. I understand.

The thing I really hate is when people say at least you have your memories. Yes, I do have my memories and that’s good, but you know, the memories are worth nothing compared to actually having the person.

Some people will ask how I’m doing every time I see them. I think that’s a dumb question. How do you think I’m doing? On the one hand, you can tell them I’m doing ok because I’m taking care of the house and cutting the grass and doing all those things that need to be done. But I don’t think they’re asking about my chores, they’re asking me how am I doing emotionally. And it’s sort of like you ought to know and I think they’d realize that if they stopped and thought about it.

We’ve programmed to ask how are you doing. Some people really want to know how you’re doing, some people ask because we’re programmed to, and some people just want you to say you’re ok.

Amy Helie’s husband Seth died on January 30, 2018, five months after he was diagnosed with grade IV glioblastoma multiforme. Amy had just turned 43. Their son Ethan was 14.

I was now faced with being a widow and a single mother. I had no idea how to navigate these waters. I had never experienced the type of grief that I was feeling then and continue to feel.

She realizes that knowing what to say to someone who is grieving isn’t easy.

I can’t say that anything that has been said to me has helped. I normally get the “How are you doing?” and “Everything will be ok, just give it time”. I remember the days following Seth’s passing, Ethan would say to me “Mom, can people just stop asking me how I am doing? How do they think I’m doing, my Dad is gone.”

What I have learned is that it is better to ask ‘How are you doing today?’. This feels more like someone is really interested in how you are truly feeling and you feel that you can give them an honest answer. The first time that I was asked in this manner, I felt that I could give an honest response and it was ‘It sucked.’ ‘How are you doing?’ feels more like a greeting and leaves you with the feeling that the greeter may not really want honesty and is not truly interested, but is just saying hi.

People also think that because you knew that your loved one was going to pass that you were prepared. There is no preparation for death and the grief that it leaves behind.

Do something to help lift the spirit of the person grieving. Little things like a text message or a phone call to just say hi or to check in on them can brighten their day. They are not necessarily going to take the initiative to reach out. They have other things on their mind; like trying to figure out how to make it through their day. A hug is always good too. As a widow, you miss those multiple times a day hugs. Getting a hug from someone can really lift your spirits.

One of Carole Schoneberg’s clients, who prefers to remain anonymous, says it doesn’t matter what people say, but that they say something. Her husband died in 2017.

A few people have not reached out beyond sending a card and I would have thought they would. It doesn’t matter what you say. You could just reach out and say you’re sorry. It doesn’t have to be overpowering. It can be a second phone call say in about two weeks. If you’re in the area, maybe call and suggest coffee. Just those little touches.

It becomes clearer and clearer who the people are that I can turn to for specific needs — this person is the right person to turn to for this. Not to put people in slots, but just to have an awareness of who I can turn to.

Carol agrees that’s it’s important to know who you can count on for support. She adds that as much as is possible you should try to surround yourself with like-minded spirits.

When a death happens, there are going to be people who will not be supportive and helpful to be around. They might have anxiety issues or they disappear or they try to tell you what you need to to do it right — “You need to feel; I wouldn’t do that; You should get rid of that stuff now.” You don’t have to be rude or nasty about it, but don’t be around those people.

Beth Van Gordon was fortunate to have lots of loving support when her close friend Eileen Rubin died on June 2, 2015. When Eileen was diagnosed with cancer, she made several trips to North Carolina to be with her and help however she could. And when she died Beth was there with Eileen’s family. It helped to be able to give and receive comfort. And then, she had to return home to Maine, thankfully, to other friends.

When I came back it was lonely but I have wonderful friends and they did reach out and they would let me talk about Eileen. Most of them knew her a little bit, because she was my oldest Portland friend before she moved away. Everybody in my close circle knew her and would let me talk about her and laugh.

Eileen and I like to hike and one of my other really good friends is a hiker as well. We did Bald Face together, which was a mountain that Eileen and her husband and I and a man I was dating tried to do twice. Each time we got turned back, one time because of ice and the other because of something else. My friend Becky and I went back and we did it. That was kind of in honor of Eileen. I miss her.

When you don’t know what to say, start here

Carol Schoneberg has several tips on what to say to someone who is grieving.

The first thing is to say I’m sorry that your loved one died. People are afraid to use words like die and death. Don’t be. What’s more important, really, than what you say is being present, being aware. Look the person in the eye. Let them know you are thinking about them.

What NOT to say

- He’s in a better place now

- You have other children don’t you?

- It will get easier

- I know how you feel (instead ask the person who he/she feels)

- It’s part of God’s plan

- Look at what you have to be thankful for

- This is behind you, it’s time to get on with your life now

- Any statement that begins with “you should” or “you will”

Some practical ways you can help a grieving person

Carol says you can offer to:

- Shop for groceries or run errands

- Drop off a casserole or other type of food

- Help with funeral arrangements

- Stay in his or her home to take phone calls and receive guests

- Help with insurance forms or bills

- Take care of housework, such as cleaning or laundry

- Watch his or her children or pick them up from school

- Drive him or her wherever he or she needs to go

- Look after his or her pets

- Go with them to a support group meeting

- Accompany them on a walk

- Take them to lunch or a movie

- Share an enjoyable activity (game, puzzle, art project)

They say that time heals all wounds, but grief sticks with you, says Althea Masteron. She lost her husband Bob to pancreatic cancer on February 5, 2013.

I remember people saying to me, wait a year and you’ll be fine. Another said it took her friend a full two years to adjust to losing her husband. I knew what they were trying to say; they were trying to help me know that I’d be fine, that time would make things easier.

Five years out from losing Bob to pancreatic cancer, I am much stronger, but I was fortunate to be strong in the first place. Still, everyday memories can bring whatever I may be doing to a halt until I gather myself together. And when times are tough – I recently lost my brother – I long so very much for the love and support that defined who Bob was. I still live in the house where we raised our children and every inch, every corner, is a memory. What’s different now from five years ago is that there are fewer instances when memories ground me to that halt. I think I can actually say that most of the time, they bring a smile.

I don’t expect to ever totally accept that this happened to Bob. I will always feel that our children and I lost him far too soon. But the passage of time does help. Bob didn’t think that our lives were about how long we lived, but rather how well we lived. I think he was right, and that helps.

Leave A Comment