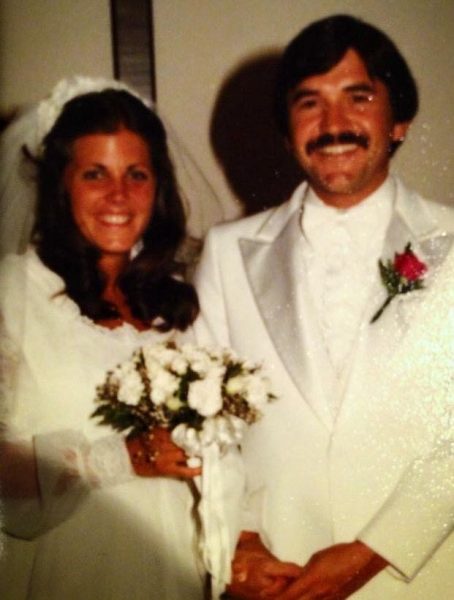

Earl and Judy Cutter

Earl and Judy Cutter first met in Paris, France. They both lived in the small Maine town of Westbrook but didn’t know each other. Earl had recently started teaching French and Latin at the local high school and had organized a class trip to Paris.

Judy, who was fresh out of nursing school, had always wanted to go to Paris. When the trip was opened to members of the community, she and two college friends signed up.

And so, it happened that one night at the Lido in Paris, Judy and Earl sat across from each other. He looked at her and told her that she had “the most beautiful eyes.”

A year and a half later, they were married. “He swept me off my feet!” says Judy. “He’s handsome and just the nicest guy.

Their life together has been rich. It still is. They raised three children, all of whom live nearby, and have two grandchildren.

Judy is Director of Admissions at a local senior care facility called Gorham House, where she has worked for more than two decades.

Earl continued to teach French and Latin and became chairman of the language department. For 35 years, he was also the voice of the Westbrook High School Blue Blazes and used to announce all of the school’s basketball, soccer and football games.

“He has such a large personality,” says former student Bob Kahler. “He was one of those teachers who is friendly, pleasant, in the hallway, saying hello to everyone.”

Bob is now principal of Lisbon Community School in Lisbon. It was Earl who first suggested he’d make a good teacher. And yes, he tries to emulate his former teacher, now friend. “Be yourself,” says Bob. “Have a sense of humor with the kids. When you make a mistake, own up to it.

A turning point

The lessons that Earl (and Judy) teach these days are having an even more profound effect on Bob and everyone else who comes in contact with the Cutters. In recent years they’ve had to face enormous challenges every single day and they do so with grace and humility.

About seven years ago, when Earl was nearing retirement, he lost his balance and fell into the lap of a fellow teacher at a faculty meeting. It was so unusual, they made an appointment with a neurologist.

Three neurologists later — in Maine, Boston and at Cornell University Medical Center — they finally found out for sure why he lost his balance.

That was August 2011. The diagnosis: Multiple System Atrophy or MSA. Judy thought the doctor meant MS (multiple sclerosis).

“We live at the lake in the summertime ,” Judy told me. “I remember because my grandson was a baby and I went down to the beach and I got on my phone and I googled MSA. I was all by myself and I just started bawling. The survival rate is six to nine years. No cure. You just treat the symptoms.”

What is MSA?

MSA is a rare neurodegenerative disorder. In fact, it’s so rare that even many doctors don’t know much about it. Earl is one of between 15,000 and 50,000 people in the United States known to have the disease. It used to be called Shy-Drager Syndrome. It usually strikes people in their 50s or 60s, but one form of it can affect people in their 20s.

There are two basic types of MSA.

1. The first type resembles Parkinson’s disease. Signs include:

- Slow, shuffling gait

- Slurred speech

- Frozen expression on the face

- Rigid muscles

- Tremor at rest

Sometimes, the same medications used for Parkinson’s can help in the early stages of this type of MSA. Unfortunately, MSA progresses much faster than Parkinson’s.

2. The second type of MSA affects the cerebellum. That’s the part of the brain that controls balance and coordination. It also affects the autonomic nervous system, which controls things like blood pressure, temperature, and digestion.

Earl has the second type. Except for losing his balance, he didn’t have some classic symptoms in the beginning. “I didn’t feel dizzy,” he says. “Fortunately, I never had that.”

And his blood pressure didn’t drop when he stood up and cause him to pass out — it’s called postural hypotension.

But he had other symptoms. “It started to affect his speech,” says Judy, “then he had problems with his bowels — they’re part of the autonomic nervous system. He also had urinary retention and [developed] sleep apnea.”

Over the past five years, the disease has progressed. Although Earl can speak it’s sometimes difficult to understand what he’s saying. His balance is now so bad he spends most of his time in a wheelchair, although he still tries using a walker and rides his recumbent bike every day.

Last Christmas (2015) they discovered that his vocal cords were partially paralyzed. They need to move when you swallow so that food goes down your esophagus instead of your windpipe. Because he was now at risk of aspirating, he needed a tracheotomy — a tube into his windpipe. At some point, he might also need a feeding tube.

Blessings

The outcome of Earl’s disease is inevitable, but that is not where he nor the rest of his family and friends choose to focus their energy. They try to take each setback in stride and see the positive in every small victory. “I didn’t feel angry,” says Earl. “I felt discouraged at first. I still have moments.”

I asked him what he did when he felt discouraged. ” I always think this could be worse,” he answered.

Judy is devoted to her husband and is his fiercest advocate. They and their children get a tremendous amount of love and support from family and friends. But it is Earl’s optimistic attitude that seems to make the biggest difference. “He’s never ever in a bad mood,” says Judy. “He’s so grateful for each and every day that we have with our family. Thank god our kids are all around us. We have a good team. And the amount of support that we have with friends. I feel like we’re blessed.”

Edgar Beem is a longtime friend. He and Earl went to high school together. Ed is a columnist for the Forecaster and two years ago, wrote a beautiful piece about his friendship with Earl. Every Wednesday, he and Earl and some other old buddies go out for lunch. They call themselves the Out to Lunch Bunch.

Ed had this to say in his column: “The first thing you learn when an old friend comes down with a disabling condition is that the person is not the disease. You’d think that would be perfectly obvious, but I’m afraid the natural inclination when you meet someone with MSA (or Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, Lou Gehrig’s disease or multiple sclerosis) is not to see beyond the symptoms to the totally normal person thus afflicted.”

A newer, but no less devoted friend is semi-retired plastic surgeon Dr. Bob Waterhouse. He and his wife knew Judy and Earl through mutual friends. When he realized what was going on, he offered to help in any way he could. Every Monday for the past two years he’s been at their house or summer cottage doing projects.

“He does all kinds of stuff for us,” says Judy. “Handrails, he built a ramp with our son up at camp. I leave him Bob to-do lists. He is our angel.”

“It started out with just a visit,” says Bob. “Unfortunately, it’s gotten to the point now where Earl can’t even replace a light bulb. Being such an accomplished guy in the past I’m sure it’s frustrating.”

If it is, Earl never shows it. “He’s so upbeat,” Bob says. “His approach is exemplary. He says he essentially embraces ‘what I am now and I don’t dwell on what I was.’ I think he lives for the moment.”

Like that moment last summer at camp when Earl was able to go swimming again. He and Bob went to New Hampshire to buy a golf cart so he could get down to the beach and into the lake. “It was like he had his old body back because balance wasn’t important,” says Bob. “He was just in there and he was able to walk along the bottom and didn’t have to worry about falling over. He said it was a moment where he just felt great because he was more like his old self.”

Day by day Earl’s disease progresses. This is not at all how he expected to live his retirement. He admits that he once asked, “Why, me?” Eventually, he was able to say “Why not me?”

“In the grand scheme of things,” he says, “it’s no big deal. In this big beach of life, we’re just grains of sand. One life, one grain of sand.”

For more information about MSA

If you would like to learn more about Multiple System Atrophy (MSA), including current research, here are some resources for you:

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

Such a touching and inspiring story, Diane. And a poignant reminder to live your life fully, every day.

You’re so right, Roxanne. They are such an inspiring family.

I’ve known Earl for about 40 yrs. He’s very close to my oldest brother Ed Beem and as you stated, the two of them along with Roland Quinlan, venture out and about on weds for lunch.

My thoughts/prayers to Earl, his wife and family. He was well liked as a French teacher at WHS and more so, he was/is a better human being. God bless Earl.

Nice work, Diane. You got the facts straight and Earl comes through crystal clear.

Mr. Cutter was my French teacher throughout my time at Westbrook High School, as he was for countless students over the years. He was a remarkable teacher and as this story proves, a remarkable man. I wish all the best for him and his very special and loving family.

Mr. Cutter was (and apparently still is) an incredible man! I loved his teaching style, his energy, and his attitude! I had the pleasures of having him as a teacher and of babysitting his kids when they were very young… I had no idea that he was going through this, and I had never heard of MSA, so thanks for the article on both fronts.

Mr. Cutter was also my French teacher. What a super teacher and wonderful man. Our French field trip to Paris was spectacular and so much fun, I didn’t want to leave… Mr. Cutter, I still wonder what my life would have been like if i hadn’t gotten on that bus to return to the states.

Mr. Cutter was one of my favorite teachers at WHS. He had an extensive tie collection (cravat to Mr. C). So one day while we were waiting for him to finish a conversation he was having in the hallway, I snuck up to his blackboard and made a column called RATE A TIE! When he came in I asked the class for a verbal number from 1 to 10 and recorded the results in the column. Mr. Cutter took it in stride and didn’t erase the column. For the rest of the school year he never ceased to wear a different, flashy tie and welcomed the challenge. It is one of my favorite childhood memories of high school. I was truly saddened to hear of his existing medical challenges but know that nothing will dampen his passion for life. Love you Mr. C!

Is a recombinant bike a recumbent bike for people that speak French? 😛

Oh, my! Thank you so much for picking that up. I have fixed.

Diane, I’m so glad to have read your article on MSA and this wonderful family. MSA needs more attention. To have to go through so many providers to finally find an answer doesn’t seem right. But that’s how it is. Hopefully this article will help with awareness. My oldest brother contracted MSA . He was a beloved history teacher in Austin Texas teaching American History.

Hopefully the Cutter family is in touch with the MSA Coalition.

And thank you for your efforts.

I recently went thru the same thing with my wife Virginia . She passed away in July. She had lost a lot of weight and developed a urinary tract infection pneumonia and congestive heart failure . It was heart breaking to watch her slip away. I knowwhat this family is going thru . We had help both physically and emotionally ,and good friends that came to see her right up to the time she passed. Her best friend Sandy was always there to cheer her up. . Her sister Benda was with her when she took her last breath . I’m so thankful for that and the fact we went places and did things before she had any symptoms of MSA

I was initially diagnosed PAF – 58 years after autonomic symptoms started. Then I went to an MSA specialist and he seems think that it is not exactly PAF. That can only mean that it’s one of the other 2 diseases in its category, and it’s not Parkinson. That leaves only MSA, but it is not supposed to start until after you are 60 – mine started when I was 11.