Leona Trinin was in her late 60s when her eye doctor told her he saw some yellow deposits under her retina. He called them drusen and said they were a sign that she would develop age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and eventually lose her sight. He was right. Within 10 years, she was having trouble seeing.

Straight lines looked wobbly and I sometimes made mistakes on color which I never used to because I was a quilter and a photographer and my color sense used to be pretty good.

What happens when you have AMD is that the macula, a small spot near the middle of the retina, deteriorates. It’s the part of the eye that allows us to see things straight ahead — our central vision as opposed to our peripheral vision.

I don’t see faces well enough to recognize people by them. If I turn my head, between shape and gait and voice and hair color I usually recognize people I’m familiar with as we get nearer to each other.

It’s a terrible problem —all those things you use your vision for every day. I drop things often. Luckily, I have some peripheral vision in both eyes so I can usually get myself through an unfamiliar place without running into too many strangers.

Looking for answers

Age-related macular degeneration is a leading cause of blindness around the world. There is no cure. Yet.

Dr. Vicki Losick, a scientist at MDI Biological Laboratory (MDIBL) in Bar Harbor, may help bring us a step closer. Dr. Losick recently became the first person to receive an award from the William Procter Scientific Innovation Fund.

Procter was a prominent entomologist who authored a massive survey of the insect and marine fauna of Mount Desert Island. He launched it in the 1920s at MDIBL, where he served as a trustee and the president.

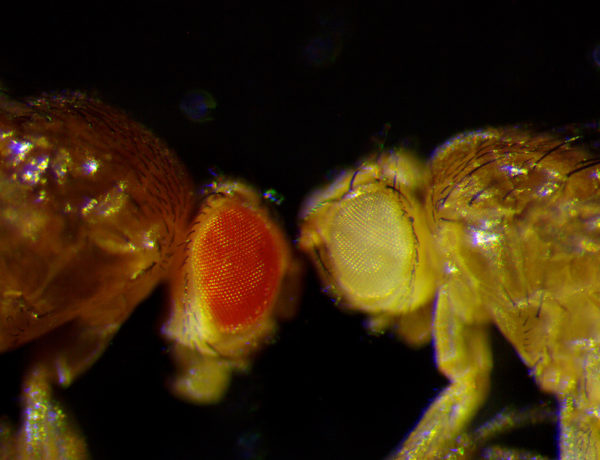

Procter was inspired by Thomas Hunt Morgan, the Nobel prizewinning scientist who founded modern genetics and established the fruit fly as a model for the study of human disease. The fruit fly plays an important role in Dr. Losick’s lab.

In earlier research, she studied cells in the fruit fly that sometimes got quite large after an injury.

What I saw was, quite to my surprise, that the cells around the center of the wound or forming scar started to grow in size. They became

— two to three times larger — cells. And in the end, what happened is this giant cell encompassed the area under the scar-like tissue. We call this cell a polyploid cell. giant

She realized that it was an entirely new mechanism for wound healing and one that might lead to new treatments. You can read about her wound healing research in this blog post

The same large or polyploid cells related to injury appear in retinal disease, including age-related macular degeneration. Scientists believe they may be an early sign of the disease.

We’re taking advantage of the fact that there have been genes linked to this disease. Our research is trying to understand what gives rise to the extra big cells and what genes are causing it. And then we hope to find ways to suppress or prevent it so you can maintain your normal healthy tissue architecture.

The fruit fly is a good model because it shares about 75 percent of the genes that cause diseases in humans. Another advantage is that it offers quick results.

We can see

changes arise within a matter of weeks, whereas in humans it takes about 60 years. In mice, it takes more than a year. So the fruit fly offers speed.

While the fruit fly may offer speed, it probably won’t be fast enough to help Leona. When I told her about Dr. Losick’s research, she said it still gave her hope.

Not for me because what’s lost is already lost. If I live much longer I would hope to not lose a lot more. So maybe a little hope for me but mostly for the people coming behind me and for my children.

The Procter Fund provides up to $50,000 for one year. In that time, Dr. Losick’s goal is to identify the role polyploids play in AMD. She then plans to collaborate with Dr. Patsy Nishina, Ph.D., an expert on retinal diseases at The Jackson Laboratory, to identify genetic or pharmacological treatments.

Leave A Comment