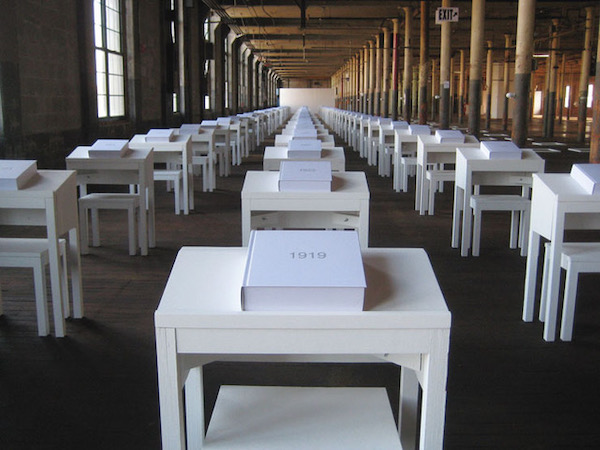

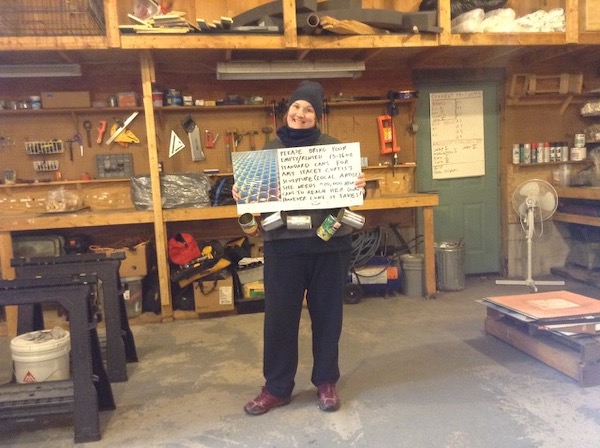

From 1998 to 2016, Amy Stacey Curtis, an artist from Lyman, Maine, worked tirelessly on an 18-year project — 9 solo-biennial exhibits of large-in-scope, interactive installation art in 9 vast mill spaces throughout Maine. In the end, she mounted 81 participatory works while cleaning by hand each historic space (averaging 25,000 square feet). Each solo biennial was a 22-month process exploring a different, predetermined theme, inviting the audience to activate each exhibit’s 9 unique installations.

Amy had been working toward new interactive works for 5 weeks in her studio, when she was debilitated by a neurological illness. It took 15 months to figure out that her brain was being attacked by untreated Lyme Disease.

As she continues to recover, Amy writes about her life and her work, now as a disabled artist, in her weekly blog The Artist Plan She shares her experiences to encourage anyone with suicidal thoughts to talk to someone and seek help. She is also trying to raise awareness about suicidal ideation as an illness, not a choice, whether the illness is psychological, physiological, or both.

In her own words, this is Amy’s story.

Four years ago, a switch flipped on in my brain. I was thinking about something like “oooh, I love what I just ate for lunch.” In the next instant, I was seeing horrific pictures of me ending my life. I couldn’t flip the switch back, not to the image of the sandwich I’d made, or anything else. All my brain could show me, as if projected all over the inside of my brain, were movies of me doing the unimaginable.

Amy Stacey Curtis, artist and writer from Lyman, Maine

I’d known how it felt to be suicidal most of my life, to obsess about ending my existence, wanting to be dead, even attempting. And through long, hard work, I’d healed from this childhood-through-adulthood c-PTSD, clinical depression, and suicidal ideation. What was happening now felt completely different. I had no interest in dying. I was loving my life, happy, light, free from my trauma, and had been for a long time. I was content, in love with my husband, my two dogs, my life, in love with me. So why was I killing myself over and over again in my mind?

For 22 months, 24 hours a day, my brain would show me nothing but non-stop, traumatic pictures of my suicide. My first doctors termed this a “suicidal psychosis,” or late-onset schizophrenia. But, ’schizophrenia’ didn’t feel right to me. And if this was a psychosis, what was causing it? As doctors tried anti-psychotic drug after anti-psychotic drug, I kept saying, “I’m not seeing or hearing things that aren’t here.” “I think there’s something physically wrong.” “I’ve been suicidal before. This doesn’t feel like that.”

After 2 psychiatric wards, 8 anti-psychotic drugs, and 15 months of schizophrenia-diagnosing doctors, we were desperate. I couldn’t see anything else in my mind, from waking to sleeping, only movies of me ending everything. Sometimes I’d see myself as I was doing it. Sometimes I’d see myself dead after I’d done it. Sometimes I’d watch from outside myself, see the whole of the act. Sometimes I’d see it happen from the inside, looking out my own eyes. This was always the scariest.

About 9 months after the non-stop images started in my brain, I lost control of my body. What started as herky-jerky movement throughout my frame, became a lag in my muscles, like I was trying to move through soft clay. While this was worst in my legs, the muscles in my face, neck, shoulders, and arms—were now doing their own thing, constantly moving, regardless of how I wanted to move them. My head would bob, my hands and wrists curl, my arms flail, my mouth twist, my jaw jut, my tongue would press against the roof of my mouth or out past my lips to the right, left, up, down…

As the muscles slowed and twisted even more in my face, it got harder to talk, then to chew, then to swallow. My tongue felt swollen though it wasn’t, and moving my mouth took great effort—more weak or paralyzed each week. I started to feel cut off like no one would understand me soon, what I’m thinking, what I’m feeling, that I don’t want to die.

No one knew what to do. Me, I didn’t care as much about my flailing arms, bobbing head, and curled lips. I just wanted the pictures of my death to stop playing. I prayed to see something else in my head, anything else. Doctors could now plainly see something was wrong with my brain. But, my difficulty walking, staying still, and speaking was a distraction, the doctors wanting to address only these things they could see. Shouldn’t we figure out the cause? the root of what’s happening? to stop the movies in my head

If I isolated myself, the hijacker in my brain would win. I talked to people on the phone, video chatted, visited with friends at the edge of my bed. If people didn’t know what to say, I asked them to tell me what they’d been up to. Though their stories and thoughts didn’t stop the movies projecting in my brain, their words were a little bit of a distraction and certainly a comfort. If they still didn’t know what to say, I asked them to just listen, while I pushed words out my mouth as best I could. It helped to express anything about what was happening, like turning a valve to relieve a little bit of pressure.

So yes, after 2 psychiatric wards, 8 drugs, and 15 months of doctors, we were desperate… when a Facebook friend sent an article about how brain inflammation can cause suicidal ideation. Was this why what I was experiencing now felt so different from the suicidal ideation I’d experienced before? How can we figure out if I have brain inflammation? If I do, how do we figure out what’s causing it? Then, how do we get rid of it? One thing at a time.

I showed the article to my primary care physician and asked her how to find out whether or not I had brain inflammation. “Let’s try reducing any inflammation to see what happens.” She prescribed an over-the-counter anti-inflammatory drug for two weeks at the safest largest dosage. During the trial, the images were more toward the back of my mind. Then, as soon as the drugs left my system, the images entered the foreground again. It wasn’t safe to stay on the drug, so she referred me to a neurologist to source the inflammation’s cause.

All tests were negative, the electroencephalogram (EEG), the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), even the spinal tap. The blood work ordered showed inflammation (without explaining where), but the neurologist said the numbers weren’t out of range enough to warrant consideration. He said, “I think you have schizophrenia.” Then, he suggested a 9th anti-psychotic drug. We wanted something to point at, “See? Something’s wrong, right here, and we know what it’s called.”

But of course, we were glad none of these somethings were found, somethings like encephalitis, Huntington’s, or tumor. Some of these things could be curable, some not, some lethal.

Soon, there was a story published in our state’s largest newspaper about what was happening to me and my husband. We hadn’t known the article would begin on the front page, a huge picture of me and our dogs on my bed. We felt extra vulnerable, then realized that more people would read the story this way, that it could help even more someones, that more someones could perhaps help us. Hundreds of readers sent emails, messages, comments, and texts, with prayers, suggestions, diagnoses, and contacts. Some sent their own resonant stories about going through mental illness, sometimes sharing these stories for the first time. With all this help, we felt less desperation—surely one of these suggestions would be the right one. We were also encouraged by the readers to keep talking to professionals about brain inflammation, about how this could be the start of everything.

Following a reader-suggested lead, we met with a naturopath to look deeper into the elevated inflammation levels my neurologist felt didn’t warrant concern: “I think you have neurogenic inflammation or ‘brain on fire,’ and this is probably the source of your suicidal ideation.”The naturopath explained that brain inflammation can be caused by many different things, viral infections, bacteria, fungi, toxins, even diet. But after seeing antibodies in my blood, he was fairly certain my brain inflammation was caused by Lyme Disease that was never treated, an infection that was now gone. He explained that when Lyme disease isn’t treated enough or at all—it can eventually cause psychiatric problems like major depressive disorder, schizophrenia, and obsessive-compulsive disorder, as well as “parkinsonism,” walking disorders, facial palsy/paralysis, speech difficulty, and dystonia (the fancy word for my curling arms and wrists). Other Lyme Disease symptoms to which I could relate: extreme fatigue, neck stiffness, muscle twitching, numbness, poor balance, increased sensitivity to light and sound, and seizure activity. “It’s essentially a brain injury I’m confident you can recover from.”

My neurologist had tested for Lyme Disease during my spinal tap, but the infection was no longer in my system—he couldn’t see it. As the naturopath explained everything, my husband and I kept smiling at each other in huge relief. We could give this horrific thing a name. And more importantly, this doctor would help me heal from it. The naturopath suggested an anti-inflammatory diet and prescribed supplements which reduce inflammation, decrease depression, and strengthen my brain function.

Seven months into the naturopath’s treatment, we saw big improvements in my movement and speech. In our quiet home, I gained more control of my body. But in places where my brain was extra-stimulated (hospital lobbies, grocery stores, crowded rooms) I still had no control. The busier the environment, the brighter the light, the louder the sound—the bigger my dance.

If it took a lot longer to gain control of my body, I was fine with that. But by now these horrific images had played in my brain continuously for 20 months. We’d tried many things to turn them off, lots of drugs, psychotherapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, reiki, community prayer, Shamanistic exorcism, even birth control pills. I couldn’t wait any longer to take back control of my mind.

Another generous friend and article reader came to our home to share how electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) helped her husband heal from suicidal ideation when nothing else worked. “You’re under anesthesia for about two minutes. They cause a brief seizure in your brain with small electric currents.” She explained how my short-term memory would likely be affected while being treated. “My husband only remembered 5 of his 18 treatments.” I asked, “Is he still himself?” She explained that he didn’t lose any of his personality, abilities, nor creativity. “It was like he was rebooted. He was still himself, but without the suicidal thoughts.” As she walked out our door, I knew this would work for me, for us. It had to. I was on the phone with my psychiatrist the next morning to get the referral process going.

As the ECT team of doctors and nurses put the oxygen mask on my face, I said “thank you” looking into each pair of eyes. I was so grateful to them. They were finally going to stop the videos in my head. Then, just as I started to get sleepy, I had the most profound feelings of trust I’ve ever felt. My brain—my life—was literally in their hands. And I thought: I know you got me, I know you won’t hurt my beautiful brain. The next thing I remember was a nurse telling me I’m done and feeling tired in a way I’d not been tired before. Then I slept and slept and slept.

The morning after my 16th ECT treatment, for the first time in almost two years, I could see something in my mind other than my suicide. It was an image of my face with different colors radiating from its center. As soon as I realized I wasn’t seeing my death, the picture of course switched back to one of my suicide. But I could swap it with my colorful face, over and over again. In four months, I was seeing the scary movies in my head only 50 times a day, and I could switch them most of the time with my colorful face. In nine months, the movies were down to 20 times a day, in 13 months, 10 times a day, in 18 months, 5 times a day, and by 22 months, 0-to-5 times a day, where it has remained for the last 3 months.

It’s hard to express how it feels to see things in my mind, things that are mine again; and what it means to have space in my head to just be still. For two years I had a ridiculous roommate who never leaves, never stops making sounds, pokes me in the shoulder repeatedly, painfully, in the same tender spot. I have the room all to myself again.

I still see the pictures of my suicide a few times each day. I can live with this for now. If it gets bad again, I will get more ECT, and it will work. My movement and difficulty speaking has continued to improve. I’ve graduated from wheelchair to walker to cane, only needed in those extra-stimulating busy places. Someday I’ll get back to “normal.” Or, normal enough.

And if I don’t, there were much worse things.

Note from Diane

If you would like to read Amy’s weekly blog posts, visit The Artist Plan and to see the incredible (an understatement) art that she produces, visit amystaceycurtis.com.

If you or someone you care about is thinking or talking about suicide, don’t hesitate to reach our for help. Contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline 1-800-273-8255. It’s available 24/7.

What an incredible lengthy ride for Amy. I’m amazed with those constant pictures in her head that she stayed positive and keep pursuing treatment. Glad the treatment is helping and wish her a wonderful recovery!

She is an inspiration, for sure.

What an awful story, but it is also a great story. I do not know how she got through this event.

Makes you wonder how many cases of Lyme Disease have been misdiagnosed and what forms the disease has taken.

The NIH needs to take a deep dive into cases with symptoms like Amy’s.

What a long haul, Amy. I am so sorry for your struggles but glad to hear that you are recovering. As someone who knows about Lyme disease from the inside out, I hope you received appropriate testing for Lyme—and by that, I mean a Western Blot with all the bands printed out and read by someone who understands what those bands actually mean—or even more advanced testing— and testing not only for Lyme (Borrelia) but for the many co-infections that frequently accompany a tick bite. I don’t understand how you could have had Lyme, never been treated with antibiotics for it, and no longer have it. That doesn’t comport with all that I know and have written about when it comes to this disease. Even years after a tick bite, people go on antibiotics to kill the spirochetes, which do a fabulous job of hiding throughout the body.

Please, Amy, and anyone who has ever been bitten by a tick, connect with a Lyme-literate physician; get the appropriate tests, look into ILADS.org (The International Lyme and Associated Diseases Society) and Lymedisease.org. for facts and new research. ‘Under our Skin’ and the follow-up film, ‘Under Our Skin 2, Emergence,’ are stunning documentaries about Lyme disease. Just about every state has support groups that can help you understand your experiences and find appropriate treatment providers.

This illness can be a killer. You may not remember a tick bite, you may not have gotten a traditional bullseye rash, a spring or fall or summer flu may have not been identified as tick-borne illness at the time, but the effects of this infection can not only cause systemic inflammation—the consequences can be neuropsychiatric, neurological, cardiac, rheumatological—or any number of things—because every organ in your body can be affected. As Amy’s story shows, failure to diagnose and appropriately treat tick-borne infections can lead to a nightmare of bizarre symptoms years later.

Amy, you are such a bright light! This story should be shouted from the rooftops, for so, so much more than Lyme Disease awareness. You are a testament to what human beings can be, and become, and especially rise to. Much love!