I really relate to Jen Dimond’s story because I, too, am an introvert and quite adept at navigating solitude and quiet spaces. But this situation is different. There are moments — more than I might have expected — when I realize how much I miss. All those interactions we often take for granted, the handshakes, the hugs, meeting a friend for a cup of coffee, lunch, a glass of wine, having face-to-face conversations. I miss leisurely strolls through grocery stores, book stores, art supply stores, and downtown Portland. What Jen wrote resonates with me so strongly. “The truth is, it’s been harder than I expected. A lot harder.” Thank you, Jen, for your story. I wish I could just walk up to you and give you a long, long hug.

How Jen is coping

The past few weeks have, to say the least, been surreal as we all learn to navigate the world according to COVID-19. As a card-carrying introvert who cherishes my alone time and as a hospice social worker trained to be calm under pressure, I was initially unfazed by the thought of minimizing outside contact. After all, I’m still going to work each day and maintaining much of my daily routine, as my work is considered essential. I live alone, so I’m used to the pleasure of my own company (not to mention my two very entertaining cats). While it became clear quickly that the pandemic was going change life as we know it, I wasn’t concerned for myself or my ability to cope, but mainly about my ability to support others through this crisis.

The truth is, it’s been harder than I expected. A lot harder. I had grossly underestimated the number of hugs I give and receive in a given day, or how essential they are not only to my work—offering a comforting embrace to a grieving family member or an exhausted colleague—but to my daily sense of balance and well-being. Human touch is powerful and necessary, and having that taken from my personal and professional toolkit has been, at times, heart-wrenching. I’m learning to find new ways to provide comfort—meaningful eye contact, standing in silence with someone—when there are no words.

I have struggled with the new and necessary limitations we’ve had to place on visitors in order to protect our patients, families and dedicated staff who worry every day that they are going to unknowingly bring the virus home to their families. While I fully support the need for these precautions, it is painful to tell families their loved one with a terminal illness is not sick enough yet for visitors, that they will be permitted at bedside only when their loved one is in the last hours and days of life. That our families are so understanding and appreciative of these rules is something I both marvel at and carry heavily in my own heart every day.

In spite of all this, most days I’m coping reasonably well and finding ways to keep moving forward even when life feels uncertain. I’m missing my gym being open, but they are posting online workouts and I’m trying to get out and walk when I can.

Some days, I’m inspired to cook and remember how much I love to be creative in the kitchen, trying new recipes or inventing my own. Making delicious, thoughtfully prepared food feels like a gift to myself (and to my friends, such as when I make too many peanut butter no-bake cookies and feel the need to do drive-by deliveries).

I decided to finally try to learn to play the ukulele that’s been sitting in the top of my closet for years, thanks to free online lessons being offered through an app on my phone (I’m not sure if this venture is going to be a great success—thankfully my day job is still intact).

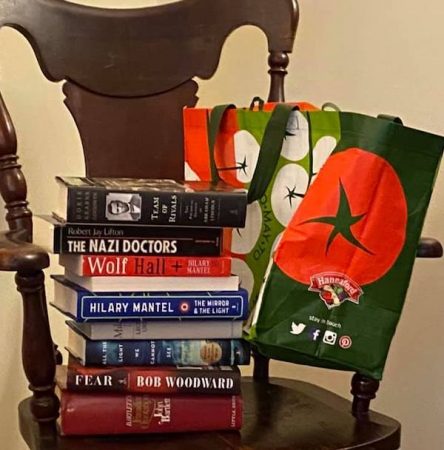

And I’m making a big dent in my reading list for the year, well on my way to my goal of reading at least 50 books in 2020. For me, these are activities that help me stay centered and give me respite from the emotional challenges of my work.

It’s tempting, however, to fall into a posture of forced gratitude, that feeling that “so many people have it worse than I do, so I should just count my blessings and be thankful.” The truth is, this is not a contest. Each of us is experiencing losses, and it’s ok to be sad about them, no matter how big or small they feel. For me, it’s missing the chance to celebrate my 50th birthday in California with my friends, and having to cancel a trip to Scotland I’ve been planning for nearly four years.

There are days when I can only muster enough energy to put on my pajamas and watch baby goat videos and Quarantine Karaoke until I collapse in bed. Or eat cereal for dinner because even making a sandwich feels like too much work. And if I emerge from this pandemic without being a ukulele prodigy or having a sparkling clean home and a freezer full of healthy meals, I’m going to cut myself some slack. I’m doing the best I can. We all are.

What I’ve learned in the last three weeks and counting is that the most powerful words I can say when everything feels like too much are “I’m not ok.” I’ve always seen myself as having an endless capacity for empathy, for saying, “I’m fine”—and believing it’s true, most of the time—and focusing my energy on supporting others while holding my own emotions close to the vest.

But the truth is, there are many days I feel like I’m hanging on by my fingernails. I found freedom in finally saying, “You know, today I’m not ok. I’m struggling,” and accepting the help that was offered to me, liberally and lovingly, by people from all corners of my life. What was most powerful to me in that moment was not only being reminded that meaningful, powerful human connection is still happening from six feet (or a computer screen) away but seeing how my willingness to be vulnerable has emboldened other people in my circle to reach out and say, “I’m not ok, either.”

In my work with hospice families, I often find that the most comforting thing I can offer is letting people know there is no one to feel during difficult times, but also that they are not alone, or weird, or broken just because they’re hurting. That same sentiment applies to each of us who is trying to find our way through this unprecedented time.

Jen Dimond

Leave A Comment