Nurses are needed everywhere in the United States, but Maine, more than any other state, faces a critical shortage.

I first became of aware of the issue last year, when my alma mater, St. Joseph’s College, announced that it had received a 1.5 million dollar challenge grant from the Alfond Foundation to create a new Center for Nursing Innovation. The Center would enhance their own nursing program but also help address a shortage of nurses and nurse educators.

This seven-part series, which is aptly called Nurses Needed, explores the reasons behind the shortage in Maine and the efforts underway to turn things around. We also get to meet some incredible nurses and see how they are taking care of people around the state.

What shortage?

A report issued by the Maine Nursing Action Coalition (MeNAC) in early 2017 projected that the state could have a shortage of 3,200 registered nurses by 2025. The MeNAC report, based on 2015 data, states that each year Maine must graduate an additional 400 newly licensed RNs and bring an additional 265 RNs into Maine from other states to address the shortage.

In 2015, Maine’s nursing programs graduated 650 new RNs. Today the number of new graduates has increased to 800. Progress is being made but it’s still far short of the numbers needed to prevent the shortage prediction from coming true.

“Even today, if every single nurse who graduated from every single nursing school in Maine applied for and got a job after graduation in June, we still would not have filled all the nursing positions in Maine,” says Juliana L’Heureux. “That’s one of the big problems.” Juliana is a retired Maine nurse who sits on the American Nurses Association of Maine Board of Directors (ANA-Maine) and is a co-author of Maine Nursing: Interviews and History on Caring and Competence.

You might think that a simple solution to the nursing shortage would be to just graduate more nurses. But nothing is ever that simple. Three major issues are at the root of the shortage of nurses in Maine.

Aging population

Maine has a higher percentage of older people than any other state. In fact, it’s known as the oldest state in the nation. The number of people over 65 is expected to increase 37 percent by 2027.

As Maine’s over 65 population continues to grow, the opposite is happening on the other end of the age spectrum. “The number of young people in Maine is decreasing,” says Paula Delahanty, the Regional Senior Director of Education and Professional Development at LincolnHealth, Pen Bay Medical Center and Waldo County General Hospital. “The birth rate is decreasing and it appears that young families are not being attracted to Maine or not staying in Maine.”

A higher percentage of older people means there will be a much greater demand for healthcare services. And it’s not only hospitals that will need more nurses to provide those services. Nursing homes and home health agencies are also feeling the crunch and looking for solutions.

Colleen Hilton is Senior Vice President of Eastern Maine Healthcare Systems (which just announced it will change its name to Northern Light Health this fall), and President of VNA & Rosscare. “VNA Home Health Hospice and EMHS are challenged with the current shortage of nurses and we do not expect it to go away anytime soon,” she said. “I spend a great deal of my time addressing the issue and have replaced many traditional nursing roles with non-clinical staff who can easily be trained to manage the same job. An example is our intake team. Once all nurses, today they are not even supervised by a nurse. Oversight is provided by a clinical director. If we are going to manage our growing elderly population with compassion and care then we need to be creative and use our resources strategically.“

But when resources continue to dwindle, then what?

Which leads us to issue #2.

Aging nursing workforce

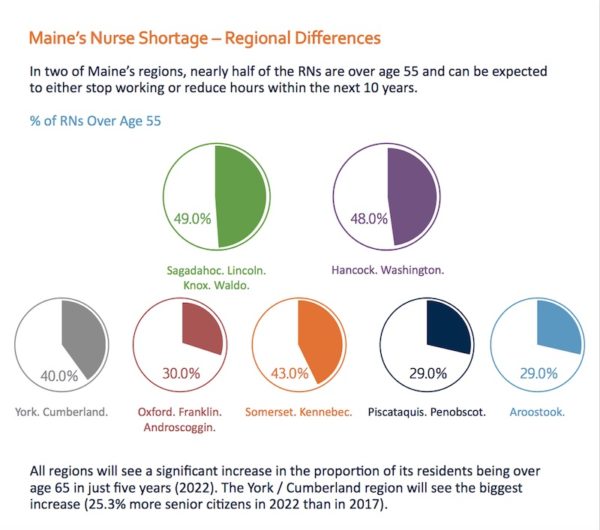

As the population ages so is the nursing workforce. A significant percentage of nurses around the state are approaching retirement age, but two regions may feel the strongest impact. Nearly half of the registered nurses in Sagadahoc, Lincoln, Knox, Waldo, Hancock, and Washington counties are over the age of 55 and expected to retire or reduce their hours in the next 10 years.

According to Lisa Harvey-McPherson, co-chair of the Maine Nursing Action Coalition, when the recession hit in 2007/2008, many older nurses chose to continue working rather than retire. “The dynamic that happened in Maine,” she explained, “is that nurses who were older stayed in the workforce longer because in many communities, particularly in rural Maine, nurses are the main wage earner for the family and they provide the family with health insurance.”

At the same time, hospitals were also impacted by the recession and couldn’t afford to hire new nursing graduates. Even as the economy improved, older nurses kept working and some of the graduating nurses had trouble finding jobs. Now the older nurses are retiring at a faster pace than other states.

Some of those retiring nurses not only care for patients, they also help train new nurses. And that brings us to issue #3.

Aging nursing faculty

Nursing faculty in Maine are among the oldest nurses in the workforce with 32% of faculty over the age of 60. In roughly the next 18 months, 25 percent of the nursing faculty in Maine will be retiring. Without adequate faculty, training new nurses becomes a huge challenge. Maine’s nursing programs have already had to turn away qualified applicants because they don’t have enough faculty to teach them. It’s not just a matter of adding instructors, it’s adding qualified instructors.

For many decades, nurses were trained in hospital-based diploma programs. It benefited the hospitals because they had a built-in nursing workforce. In the sixties, the ANA began recommending that in order to become a registered nurse, you needed a baccalaureate degree.

“The research demonstrates that for nurses to become nurse managers, chief nursing officers, to work in independent practices — without a doubt it’s the baccalaureate-trained, university-based programs that produce nurses who excel,” said Juliana. “Many move on and want to become nurse practitioners. It’s all about academia.”

Because it was difficult for some people to attend a four-year college program, community colleges began offering two-year associates degree programs. The hospital-based programs were eventually phased out and replaced by the degree programs. Programs for licensed clinical practical nurses were also phased out.

According to the Maine Board of Nursing, there are now 14 approved RN nursing programs in Maine. Seven offer associates degrees (ADN) and seven offer baccalaureate degrees (BSN). Depending on the program, to be a member of the faculty, you generally need an advanced degree.

“Faculty at colleges offering BSNs need to include a certain percentage of nurses with doctorate degrees,” explained Lisa. “At the Associate degree level, there needs to be a percentage of masters degree nurses.”

Sue Henderson, who was a nursing professor at St. Joseph’s College for 35 years and retired in 2011, said getting an advanced degree can be challenging, but it’s a whole lot easier than when she went to school. “It’s easier because of online programs,” she said. “Until the mid-80s, the nearest Master’s program for nurses was in Boston. Then USM developed one. I know people who went to Texas to get doctorate degrees, where now they can do online programs and they may have to go

In addition to needing more faculty, nursing programs must also make sure students get enough clinical experience in a hospital setting and also out in the community. That, too, can be a challenge.

Facing the challenge

If you know a good nurse, you know that facing challenges is what they do best. This triad of issues — aging population, nursing workforce, and nursing faculty — is daunting, but already, nurses have come up with some possible solutions and seen some progress.

We’ll take a look at those in the next segment of Nurses Needed, which will run Wednesday, May, 2, I’ll also tell you about a new partnership between a hospital and a college that hopefully, will be a win, win, win situation for hospitals, colleges, and students.

Friday, May 4, we’ll hear from several men in nursing about why they became nurses, barriers they may have encountered along the way, and how they would encourage other men to consider nursing as a career.

Monday, May 7 will be about advanced practice and community nursing.

Wednesday, May 9 we’ll explore the current status of public health nursing in Maine.

Friday, May 11, we’re going to show our nurses a little love. If you have a story you’d like to share about a Maine nurse, send it to me.

Monday, May 14, we’ll wrap things up with a look back at the history of nursing in Maine.

A great article for what will surely be a great series. Thanks Diane.

Thank you Liz. I hope so!

Looking forward to the next one. I went to St Joe’s and I had no idea what Maine was up against with the nursing shortage. I look forward to reading about the creative solutions.

Thanks Barbara!

I am 65 and plan to keep working until I cannot. I am working in geriatrics, LTC and skilled, which is very demanding. Unfortunately with the nurse shortage, there is the decline in the use of LPNs, and all state programs for education have become extinct . When I first entered nursing, LPNs worked side by side with RNs in all areas. I worked at MMC for 6 years in nephrology. We were a welcome and respected part of the nursing team, and would be part of the solution to taday’s shortage.

Margo, Thank you for your comment (and the hard work you do). I’m going to pass along what you said to one of the nursing leaders and will let you know what she/he says.

In the late 60’s I started my Master’s degree at NYU part time. I received a phone call from Martha Rogers explaining to me that if I went full time, the Nurse Training Act would pay my tuition and also provide a stipend for living. Lyndon Johnson had enacted the Nurse Training Act as part of his Great Society legislation in order to increase the number of nursing faculty. This gave the nursing profession a great boost. Many of his other programs did a very great deal for the health of our nation, such as the development of neighborhood health centers and support for preventive health for young children. This was is in addition to Medicare and Medicaid. Lyndon Johnson had a commitment to the health and well being of our nation that seems sorely absent today as evidenced by the debacle about funding for expanding Medicaid and treating the opioid crisis and acting to prevent child abuse by supporting robust programs. Since the 60’s we have learned a lot about measuring outcomes and designing care that is cost effective, but our state government seems at war with the those who are poor or vulnerable.

Hi Diane,

I recently saw your segment on News Center 207 program. The portion of the aging nursing faculty is something the state of Maine and the UMaine system has the ability to improve upon.

The UMaine system requires for entrance into a graduate Nursing program:

– Baccalaureate degree in Nursing

– G.P.A of 3.0 on a 4.0 scale

– Undergrad course in statistics within 5 years

– Undergrad course in total health assessment

– MAT or GRE

– Resume

– Personal Interview

(along with general admission requirements)

As a bachelor prepared Registered Nurse in Maine I hold a leadership position and with that I do perform clinical work. Myself and others who I have spoken with put in long hours, work overtime, and are already feeling the effects of the nurse shortage in the state. As someone who would love to advance and obtain a Masters in Nursing through a local school with the ability to teach someday, the admission criteria has the ability to be revised.

I would propose the UMaine system look at their criteria for admission into the Masters in Nursing programs. I would propose the elimination of the MAT or GRE if the following is met:

– GPA 3.5 or higher

– 3 years of work experience as a Bachelors prepared Registered Nurse

If the above criteria is not met, the MAT or GRE would be required.

The change in the admission criteria would allow more to obtain advanced degrees. In order to become a Registered Nurse, we must already pass a national exam.

I hope my feedback can be passed along to the UMaine system.

Please let me know if you are able to help!

One o the most shortsighted and ill-advised initiatives by the UMS was to close the Associate Degree nursing program in Augusta and force the UMA campus to adopt the BSN curriculum and TV teaching of faculty from UMFK. The then-President of UMA is now gone. Decisions about nursing at UMA were being made by administrators with no health care background. The model used to hire computer science faculty (“gig-based”) does not translate to nursing. These administrators were biased against nursing as an academic discipline because it cost more to run a nursing program than it does to fund an art program or a music program. The decision was made to bolster the enrollment numbers of UMFK, a small campus of the UM system, and not taking into account the needs of the Kennebec Valley or central Maine. Fort Kent has its own set of challenges, not the least of which is an insular curriculum.

Also, the wages for nursing faculty in Maine are about twenty per cent lower than other states, as well as being lower than comparable male-dominated academic disciplines within Maine. Until the system recognizes this inequity nothing will change.