Eleven years ago, at the age of 56, Leo Glaude had a stroke. It happened at work. His coworkers found him outside leaning against a tree. They called 911 and then called his wife Beverly.

She rushed to the hospital and the moment she saw her husband, she knew what happened. “His mouth was drooping on one side,” she says, “and he was trying to say something to me and I didn’t understand a word. I knew then that he’d had a stroke.”

Leo spent a few weeks at Southern Maine Medical Center (SMMC) and then was transferred to New England Rehabilitation Hospital in Portland. That’s where he underwent several weeks of intensive therapy and that’s where Beverly had some of her darkest moments.

When he was still at SMMC, she noticed that Leo started to turn on her. “He’d make nasty remarks,” she says, “and that’s not like him. I’d think, who is this person?”

At New England Rehab, things got worse. She knew he didn’t mean it, but it still hurt. One day, an occupational therapist suggested that instead of going right to his room when she visited, Beverly should wait by the nurse’s station. She would wheel by with Leo and Beverly could join them. At first, Leo wasn’t happy to see her, but one morning, he smiled and said, “Hi babe.”

“I knew then that it was going to be alright,” Beverly says. “Up until that point, I was not sure.”

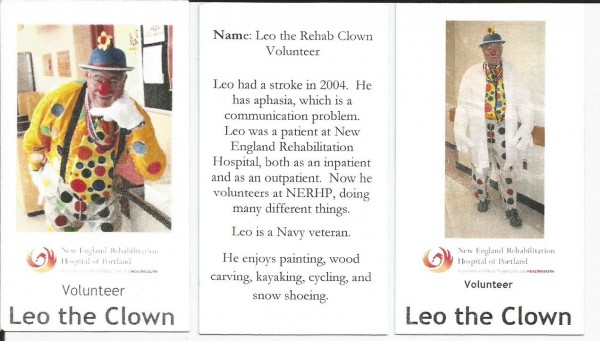

He’s a far cry from those early days of recovery but Leo is still not the same man he was before his stroke. Fortunately, he wasn’t left paralyzed but his body is weaker. He has aphasia, which means he’s lost some of his ability to communicate. He can’t read well or write and has trouble speaking and understanding what others say.

Beverly had been warned that friends might drop away, and some did. Other couples, mainly. “I figured out that it’s a lot easier to be without Leo than it is to try to figure him out,” Beverly explains. “It’s a lot of work.”

Individually, they both have friends who have stuck by them. For Leo, two former co-workers who still include him on fishing and camping trips are especially important. Getting away is good for Leo and for Beverly.

Leo also volunteers at New England Rehab as Leo the Clown. And together, he and Beverly attend an aphasia support group. In addition, Beverly has her own support group, which has been a lifesaver. “You need a place to vent and venting in front of your loved one is not the place,” she says.” I go there and I cry and I laugh and sometimes people will give you pointers to try different things because you definitely run out of ideas.”

In an instant, life changed for Beverly Glaude. For Salah Zayed, it was a slightly more gradual process. Ten years ago, his wife Hilary, now 61, fell from a horse and suffered a traumatic brain injury. Only, as is often the case, symptoms did not begin to emerge right away and they both thought things were fine at first.

Within weeks, Hilary could no longer walk or talk and ended up in the hospital. That’s when it hit Salah that something was very wrong. “At first, there’s a big denial,” he says. “You do not believe what is happening to your family. I didn’t understand what was going on. I thought they could fix it.”

Doctors, rehab and support — a lot of support — helped them understand and accept the fact that things were never going to be the same. To provide the support Hilary needed, Salah left a managerial job to take on another position with fewer demands and less pay.

They’ve learned to manage and adjust, but there are still bad days. Accomplishing one task, such as speaking to a group about her injury and the changes in her life, for instance, can be so exhausting that she spends days in bed recovering.

Salah has come to realize that before you can care for somebody else, you need to take care of yourself. “Keep a good schedule for yourself,” he recommends. “Take a break, once in a while go out with your friends. Maintain a hobby. Don’t erase everything from your life.”

Along with his initial denial, Salah has passed through several phases, including feeling angry. “Asking why us?” he says. “The anger and feeling like there was no one there to help us. I had to be the strong one and stay positive and sometimes take things lightly.”

Anger is a topic that often comes up in support groups. Judi Stevens is the volunteer facilitator of a caregiver support group at the Cancer Community Center. She took on the role about four years after her husband Greg died of a brain tumor. She’d been his primary caregiver for nearly two years.

Anger is a topic that often comes up in support groups. Judi Stevens is the volunteer facilitator of a caregiver support group at the Cancer Community Center. She took on the role about four years after her husband Greg died of a brain tumor. She’d been his primary caregiver for nearly two years.

Caring for someone may be difficult, but it’s not only the caregiver who can feel angry. Sometimes it’s the person who has become ill or disabled. “As a caregiver, you might be the only person they feel safe expressing those hard emotions around,” says Judi. “I always encourage people to not take it personally when their loved one expresses anger. They’re angry at the disease, not at you.”

And, in Judi’s experience, caregivers often carry a lot of guilt. About being healthy when their loved one is sick. About not being able to make things better. About being tired and grumpy at the end of a difficult day.

“Often when we start a group session,” she says, “the first thing someone will say is, ‘Caregiving is so hard!’ Then they immediately feel guilty about complaining.”

There is a common thread in these stories about Beverly and Salah and Judi. Who understands what you’re going through. Who can say, yes, it’s hard work being a caregiver. You’re not alone.

Leave A Comment