The route to college was a circuitous one for Rabih Dow. Literally. In order to catch a bus to Boston College, he had to circumvent a couple of city blocks rather than simply walk straight ahead and cross one street. That’s because Rabih is totally blind and in order to cross that one street safely, he had to go to the nearest intersection with a traffic signal. The white dots on the painting above, which was done by Rabih, represent the tip of his cane as he makes his way up the sidewalk, across the street and down the other side to the bus stop.

The dark masses are the buildings he passed along the way, which he couldn’t see but imagined as dark masses that faded into the background or up into the sky. He chose the blue-green color not because it is the color of sky but because he thinks it is a pleasing color combination. All of his paintings are done on glass, because of its fragility. “It reminds me of ourselves,” he says. “We think we’re indestructible, but we’re not. The round shape is also important for me because it reminds me of the plane on which a blind person travels. Think about that.”

Rabih was born with many talents, both intellectual and artistic. He was also born with the ability to see. In the milliseconds it took a bomb to explode, in 1982, when he was only 16, he lost his sight, his left hand and his younger brother. Their home was in the war-wracked country of Lebanon. Rabih says that as a boy he never really dreamed about his future, only that he and his family would live to see another day. His boyhood abruptly ended on the day he lost so much.

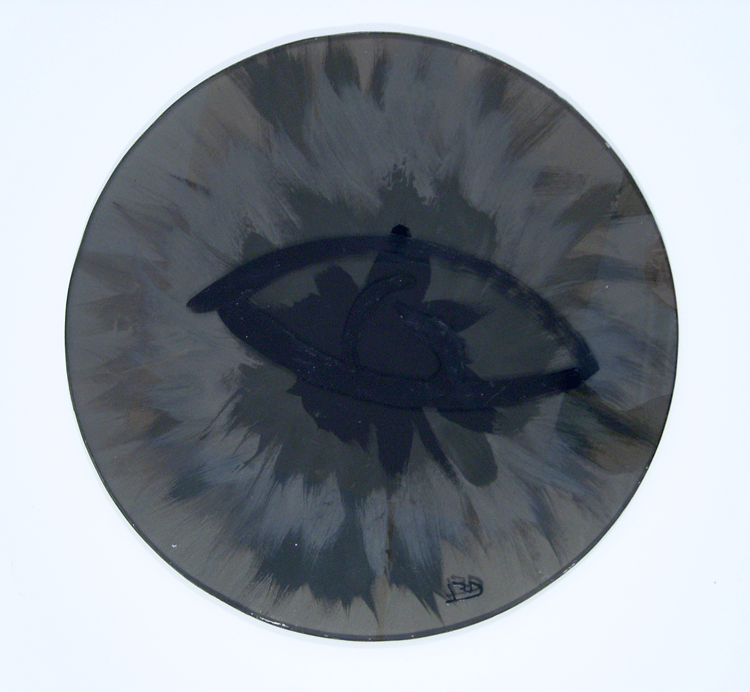

Several of Rabih’s paintings are of eyes. In this one, Onset, he says he is trying to show that “although the eye is at the epicenter of vision loss, the effects of blindness reverberate deep and wide, in us, on us, and from us.”

After his traumatic injury, he was airlifted to Italy with 62 other badly injured children and underwent surgery. He still had a little bit of sight left and was due to have more surgery in the United States, but the US Embassy in Beirut was bombed, destroying, among other things, Rabih’s paperwork. His trip was delayed four months.

He and his father finally made it to Boston, only to find out that the window of opportunity for additional surgery was gone. So was Rabih’s tiny sliver of remaining vision. He had already plunged into total darkness.

The painting above describes what it’s like to be blind, at least for Rabih. It may look black and gray, but in reality, the background is a maroonish-grayish hue. “That’s the color of blindness as I know it,” he explains. “Blindness is not colorless.”

When they realized that nothing more could be done to restore his sight, Rabih and his father planned to return to Lebanon, but it was decided that, instead, Rabih would stay behind and attend the Carroll Center for the Blind in Newton, MA.

Being left alone at 17 was a critical moment in Rabih’s life as a blind man. Not only could he not see, he could only speak a few words of English. But there were crucial advantages. “When you’re with your own family and something happens to you everybody is comparing you to the way you used to be and seeing the losses in you, the tragedy that befell you,” he says. “Here, nobody knew you before. Every day they see the potential, the possibility. You can’t help but be affected by that. Our impression of ourselves comes from other people who view us.”

In his painting Stepping Off, Rabih shows a white cane poised on the edge of a step that seems to drop off into nothingness. (By the way, he uses a stencil whenever he paints a cane and relies on sighted people to help him with placement and color mixing.) The painting used to hang in his office at the Carroll Center, but it unsettled so many people he took it down. You don’t need to be blind to understand what it’s like to experience a life crisis. Rabih says he tried to portray that moment when we are still reeling and don’t know where the next step may take us.

“It could be into a puddle of water,” he says, “it could be some dried leaves and it could be a leap into the unknown. It’s frightening. Of course it is. I always say to people you have a choice. You can sit on the steps if you want, but is that how you’re going to live?”

Rabih chose to leap into the unknown. After he went to Boston College and graduated with a degree in 20th Century Political and Intellectual History, he returned to the Carroll Center, where over a 20-year span, was an adaptive communication instructor, fencing coach (yes, fencing) and until recently, Director of Rehab Services and International Training. He also completed graduate coursework in intercultural communications at Lesley College.

In many ways, Rabih continues to leap into the unknown every single day. Crossing a busy street for the first time, for instance, or flying to another country to attend a conference or accepting a new job and moving to a new city.

A few months ago, he and his wife Lori, who is from Maine, moved to Portland, where Rabih is now Director of Program Services at the Iris Network. He has spent the last nearly 35 years of his life meeting the challenges of new situations and helping scores of other people who have also lost their sight. That won’t change, but an opportunity at the Iris Network offered him something he is always open to — new possibilities. “There is restructuring taking place both at the Iris Network and at the state level of vision rehab services, in general,” Rabih explains.

In addition to the many services it already provides, in September the Iris Network will begin a new center-based program jointly sponsored with the Department for the Blind and Vision Impaired (DBVI) and funded by the Rehabilitation Services Administration in Washington, D.C.

Whatever their needs are, Rabih would like people who are struggling with vision loss not to be afraid of it and to ask for help. “You’re not alone,” he says emphatically, “and we live in an age right now where we’re much more connected and able to tap into that communication more than at any other time, so take advantage. Benefit from the collective knowledge of people who work in a place like the Iris Network because they can share with you the experiences of others and the research that’s been done, not just here but around the world.”

Rabih’s painting Adrift shows an empty boat drifting in a deep dark sea against a starlit sky. He says whenever we suffer a significant crisis such as blindness, we are often “adrift until we recover sufficiently to react to it. Rehabilitation guides us through such a crisis. It helps us regain control over a life that had gotten out of control.”

Blindness is a comprehensive disability that can be overwhelming because it affects everything a person does, even something as mundane as trying to choose a shirt that isn’t soiled or making a cup of coffee in the morning.

But Rabih makes an important distinction. “Blindness is a disability,” he says,”but it’s not an inability. It’s very different. VERY different.

For more information

You can find out more about the services offered by the Iris Network on its website, by sending an email or by calling (207) 774-6273.

Rabih loves painting, something he was interested in before he lost his sight and his hand. He believes art is a powerful medium that can help people begin a dialogue about what it means to be blind. “I translate something I know about because I had vision. I have that memory,” he explains. “I try to communicate visually what I “see”/experience now as a blind person.”

If you’d like to see more of Rabih’s artwork, he invites you to visit his personal website.

Leave A Comment