During a routine checkup when she was in her 80s, my late mother’s doctor picked up a heart murmur. He sent her to a heart specialist who ordered some tests, including an echocardiogram (ultrasound). The diagnosis was aortic stenosis. I’d never heard of it before, but it’s something that can develop with age and happens in about three percent of people over 75.

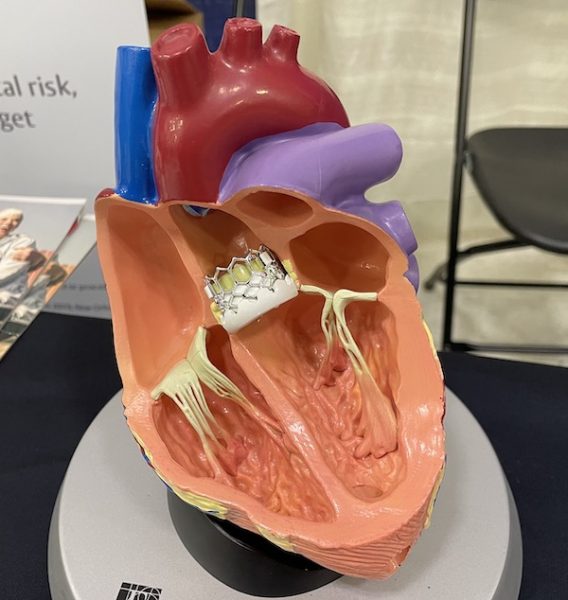

Anatomy of the heart

Your heart has four valves — aortic, tricuspid, pulmonary and mitral. Their job is to see that blood flows into your heart from your lungs and then flows out of your heart to the rest of the body. It’s important that the blood moves in only one direction. The aortic valve is what you see in the image above. It allows the blood to flow away from the heart.

Inside the valve are three leaflets or cusps that open and close with every heartbeat. When we are young, the leaflets are strong and thin — almost see-through. They’re also very pliable, says Dr. Scott Buchanan, Chief of the Division of Cardiovascular Surgery at Maine Medical Center.

The ideal valve opens completely during systole when the heart contracts and closes completely during diastole, when the heart relaxes. There should be no resistance to blood flow coming out of the heart when you want the heart ejecting, but there should infinite resistance to blood washing back into the heart between beats.

Scott Buchanan, MD, Chief, Cardiovascular Surgery, MMC

Nobody has an ideal valve, he says, and even with a normal one there’s a little resistance and sometimes a “little wisp of leaking”. As we get older, our valves can get a bit beaten up and some people will develop aortic stenosis. The condition is not related to how you live your life, it’s the luck of the draw and, in some cases, may have a vague genetic component.

The reason it happens is calcium gets deposited in the leaflets themselves, which thickens them and prevents them from opening, Left to its own devices, it’s a fatal problem because it gets to the point where the heart can’t force the leaflets open.

Dr. Buchanan

Developing aortic stenosis is a fairly slow process that can go on for many years. It is most likely to show up in people in their 70s or 80s. In time, it causes heart failure, which is when the heart muscle becomes weak and unable to pump the blood your body needs to survive.

Symptoms of aortic stenosis

My mother had no symptoms, which meant her aortic valve wasn’t narrowed enough to cause a problem, but she was closely monitored every year. These are the main symptoms we were told to watch for:

- Shortness of breath

- Chest pain, pressure, or tightness

- Fainting spells or feeling faint, especially upon exertion such as walking upstairs

- Swollen ankles

By the time someone does develop any of the above symptoms, Dr. Buchanan says they generally have a 50/50 chance of surviving another year. The only effective treatment is aortic valve replacement.

Aortic valve replacement options

When my mother was diagnosed, her only treatment option was open heart surgery to replace her aortic valve, which she steadfastly refused. Today many people are given another option — a minimally invasive procedure called a transcatheter aortic valve replacement or TAVR.

Simply put, the surgeon makes a tiny incision in the groin and threads a small flexible tube into the femoral artery and up to the aortic valve in the heart, where the new valve is expanded into place.

The benefit of TAVR is a much faster recovery. People spend one night in the hospital and go home the next day with a bandaid on their leg. Another really big sea change that’s happened in the way the procedure is performed is that many are now done without even putting the patient to sleep.The anesthesiologist can keep patients comfortable and still, but they’re actually awake. They recover quicker, there’s less nausea and vomiting, and they’re sitting up having dinner at five o’clock.

Dr. Buchanan

In the picture above, you can see what a TAVR valve looks like up close. The actual size of this particular valve ranges from 20 to 29 millimeters. In the picture below, you can get a sense of where it is placed in the heart.

When TAVR was first introduced around 2012, it was reserved for frail elderly people who were considered high risk for complications or death associated with open heart surgery. Over the past ten years, it’s become an option for younger people and those who are considered intermediate or low-risk patients.

However, they don’t have long-term data on how long the TAVR valve will last as they do on surgically implanted valves. For that reason, there is an age threshold.

None of us in the business is comfortable with doing a TAVR on a 50 or 60 year old. Those folks ought to have the traditional approach because it’s a tried and true approach.

Dr. Buchanan

Age is not the only risk

Aortic stenosis usually happens in older people, but younger people are also at risk, particularly if they have something known as a bicuspid valve. As I mentioned, the aortic valve has three leaflets, but when someone has a bicuspid valve it means two of the leaflets are fused together. It’s usually an inherited condition.

Bicuspid valves tend to run in families. When I see a patient with a bicuspid valve, I recommend that first order relatives get echocardiograms at some point in their young adult life. With three leaflet aortic stenosis, the kind of thing that we see in the 75 to 85 year old range, it’s less genetic.

Someone with a bicuspid valve is much more likely to show signs of aortic stenosis in their 50s or 60s. As for the rest of the population, as you age, it’s not inevitable that you will develop aortic stenosis, but it’s important to pay attention to any symptoms you might be having.

If you have chest pain, trouble breathing when you exercise, a sense of dizziness or fainting, get evaluated, don’t ignore it. We have some amazing tools and techniques to fix aortic stenosis and restore a person’s quality of life.

Dr. Buchanan

If you’re interested, Edwards LifeScience, one of the manufacturers of TAVR valves, has an animated video of the procedure.

Hi Diane, thanks for this post. I found out a couple of years ago that I have aortic stenosis and at some point will need a valve replacement. I had my annual echocardiogram this past week. Your explanation of this condition simplified what my PA at my cardiologist office was trying to tell me yesterday.

Thanks. I’m really enjoying your posts.

Sincerely, Susanne (Redlon) Arvidson