From the moment he was born 11 years ago, Miles Zelasko’s parents sensed all was not right. “You could tell he was an uncomfortable baby,” said his mother Celeste. “Pretty early on we knew he was having immune issues. He was having lung issues. He was put on inhalers when he was pretty young and different types of asthma medication. He couldn’t handle any smells. He couldn’t handle noise. He would cry. He couldn’t be outside in the sunlight. He had a really hard time sleeping and then at nine months he had a red rash all over his scalp.”

No one could figure out what was wrong. It never occurred to anyone that it might be Lyme Disease.

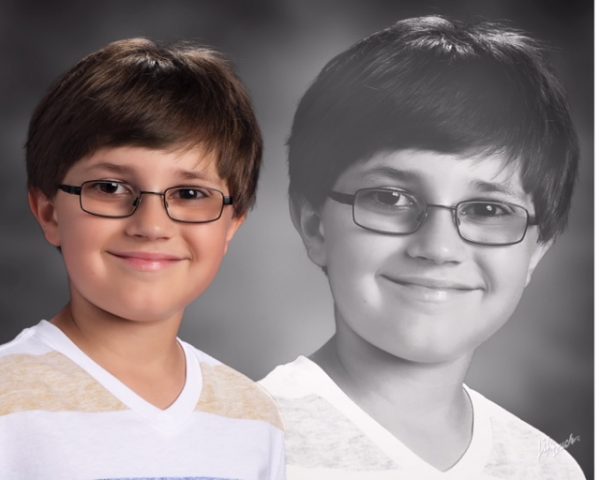

Miles’ eyes started turning in because the muscles had weakened. He was in glasses before his second birthday. It was always something new and troubling. “He was having pain in his ankles and his feet,” said Celeste. “His knees were aching and he had inflammation over his entire body. He had swollen joints in his fingers and he was starting to have hair loss. He was also having rages — kicking his feet and screaming, just outbursts out of nowhere.”

As more and more symptoms cropped up, the same thing was happening to Celeste. Over the years, beginning in 2004, the year before Miles was born, she had dealt with several strange symptoms, that like her son’s, no one could figure out.

She developed high blood pressure and a wide range of allergies. She was also diagnosed with a condition called POTS, which affects the autonomic nervous system. It’s not curable and causes a host of symptoms, including GI upset, chest pains and sensitivity to temperatures. For the most part, the symptoms came on gradually, but in late 2011, they blossomed with a vengeance.

“I got sick in November and went through six months of different specialists and they weren’t able to pull it together,” Celeste explained. “I started doing my own research and went to my physician and said I feel like I either have MS, Lyme or lupus. He gave me an extremely hard time and told me it was just an anxiety disorder.”

Celeste decided to see a Maine doctor she’d heard was well versed on Lyme Disease. “He said he could almost guarantee that I had it and at this point, it had set in,” she said.

When Celeste was diagnosed, she realized that Miles might also have Lyme Disease. Blood tests were positive for Bartonella, a co-infection that is also carried by ticks and sometimes seen alongside Lyme and other tick-borne diseases.

The challenge of getting a diagnosis

Let’s stop for a moment and talk about some of the challenges people like Celeste face in getting a diagnosis (and also, proper treatment.) To begin, why, if Lyme Disease was discovered in 1975 — 41 years ago — is it so difficult to get a diagnosis?

Celeste saw at least 100 doctors over the years, trying to get to the bottom of what was wrong with her.

Dr. Sarah Ackerley, a naturopathic doctor in Topsham, Maine, is not one of Celeste’s doctors but she sees a lot of patients with Lyme Disease. She says there are several issues that make getting a diagnosis challenging.

One is that the laboratory tests are not always reliable. The CDC currently recommends a two-step process.

- An enzyme assay called EIA. If it’s negative, there are no further tests.

- If the EIA is positive or not conclusive, a Western blot test is done.

For a positive diagnosis, both tests have to show evidence of Lyme Disease antibodies.

Dr. Ackerly believes the two-step process misses a lot of infections. “I think that we’re not necessarily looking for infection,” she explained. “We’re doing screening testing which is a different thing. It’s kind of like a pap smear, which is a screen, versus a biopsy, which we do when there is an abnormal pap smear. We’re using a screening that isn’t necessarily accurate for diagnosis.”

Another issue is the nature of the spiral-shaped bacteria (spirochete) that causes Lyme Disease. Its name is Borrelia Burgdorferi. Sounds regal, but it’s anything but. Borrelia has the ability to burrow deep into tissues and hide itself. “It can embed deep into the joints,” said Dr. Ackerly. “It can embed deep into the central nervous system tissue, into neural tissue, which is why we see the very complex range of symptoms with Lyme Disease.”

Borrelia can also make itself immune from antibiotics by turning itself into a microscopic cyst. When it’s in the form of a cyst, symptoms disappear and a person may think there is no more infection. But when it no longer feels threatened it can turn back into a spirochete and symptoms may reappear.

Celeste tried to think back to when she might have encountered a tick. She recalled that the year before Miles was born she had a bulls-eye rash. She and her ex-husband had just moved back to Maine from the South and didn’t know about Lyme Disease. “We wrote it off as a spider bite or another bug bite,” she said, “and didn’t think about it twice and then the bulls-eye went away.”

For about two weeks, she also had flu-like symptoms. “Fevers, aches, chills,” she described. “It really mimicked the flu but nobody else in my house was getting it. I was the only one who got it, so that should have been a red flag.”

The symptoms went away but eventually, other symptoms surfaced. In 2011, when they all lit up, a lot was going on in her life — a job change, surgery — so it’s possible her immune system was not in top shape. It’s also possible the symptoms were triggered by another tick bite. There isn’t always a bulls-eye rash.

As for Miles, it’s likely that Celeste passed on her initial infection to him when she was pregnant. According to the CDC, “Lyme disease acquired during pregnancy may lead to infection of the placenta and possible stillbirth; however, no negative effects on the fetus have been found when the mother receives appropriate antibiotic treatment.”

Celeste didn’t know she had Lyme Disease, so did not get any antibiotics during her pregnancy.

Controversial treatment

Once she got the diagnosis, she was immediately started on a low dose antibiotic. Because she had gone so long without being diagnosed and had so many symptoms, she decided to contact the International Lyme and Associated Disease Society (ILADS) to find a Lyme Disease expert. She found one in New York.

For the past four years, Celeste has been on multiple medications. “I’m now on two antibiotics and an antimalarial drug,” she said. “I have to stay on a viral medication and a fungal medication to keep all the different viruses in check. I also have to keep my immune system at bay and I’m on a strict diet because I’ve become allergic to almost everything. It changed everything but I guess I’m one of the really lucky ones that I’ve been able to just pull through.”

Lucky because except for her severe food allergy, she is probably 90 percent better.

Miles has also been on antibiotics and other medications since his diagnosis. “He’s had three years of treatment,” said his mother. “We see his symptoms have just gone down, down, down and now he has very few things at all. He’s still on his asthma medication but that eventually we’ll see if we can get rid of that, too.”

Miles sees Connecticut pediatrician and Lyme Disease specialist, Dr. Charles Ray Jones. Dr. Jones says the usual duration of treatment is one to three years. “What’s important,” he said, “is to treat continuously, not stopping until all symptoms are gone. “One of the worst things one can do in terms of treating almost any disease, but especially infectious diseases is to stop before all the organisms are eradicated — before all symptoms are gone. If one stops prematurely, then one has to assume the organisms that are there are left over are the ones that are more resilient and more likely to mutate into even more resilient forms. They’re the ones that are often resistant to the antibiotics that have been successfully used in the past.”

A major issue is that infection, not just one carried by ticks, can trigger an autoimmune reaction and affect the whole body. “That can be easily treated by discovering exactly what the offending organisms are,” said Dr. Jones. “They may not be Lyme, they might be candida Albicans or one of the herpes related viruses, or any of the tick-borne organisms. The main thing is that in order to treat appropriately and effectively, one has to identify all of the offending organisms and treat them all together.”

Treating Lyme Disease with long-term antibiotics is a controversial topic. One camp believes that chronic symptoms can develop in some patients after they’ve had an acute infection — they call it chronic Lyme or post-Lyme syndrome — and that those people need to be put on a long-term course of antibiotics. The opposing camp believes chronic Lyme doesn’t even exist and that a short-term course of antibiotics (Doxycycline) is all that is necessary to successfully treat an acute infection.

Dr. Ackerly says many patients are treated successfully, but not all. She doesn’t understand why there is any controversy, especially since long term antibiotics are already used to treat other infections. The usual course of treatment for TB, for instance, is six months of antibiotics. “It’s why it makes me so surprised that doctors don’t understand long-term antibiotic therapy,” she said. “It can sometimes be an effective tool for these kinds of infections that have very complex cloaking abilities and can hide in the tissues.”

Until there are better ways to diagnose Lyme Disease and other tick-borne infections and until the medical community can agree on the best way to treat them, people like Celeste and Miles will continue to suffer.

“It’s very upsetting to me and my patients,” said Dr. Ackerly. “Their family practice doctor or their internist or their gynecologist doesn’t think this is going on and they’re going crazy. They feel like there is something wrong with them and they are being told this isn’t true. People are really questioning and upset and frantic about what to believe.”

Something Celeste Zelasko understands all too well.

Thanks Diane for doing this article.

Thanks to Celeste and Miles for always help raise awareness and a friend to many in the Lyme community.

Always wishing for better health and great days ahead. ♥ to the this Lyme fighter and her son Miles who is a great, brave warrior!

Thank you Mary Ann <3

1975 was 41 years ago….not 31. Might wanna correct that…

Thank you! Hundreds of people including me have read this post and you were the first to pick up (or at least point out) that typo. I’m grateful.