Last year, my family had some unexpected medical expenses.

The bills began to add up after I had my annual mammogram. Because there were some suspicious looking calcifications, I was called back for additional views. Next, I had a stereotactic biopsy, which was positive for DCIS (ductal carcinoma in situ or stage zero breast cancer).

After consulting with a breast surgeon and getting a second opinion, I opted for a lumpectomy. About an hour before the procedure, I had to go the radiology department for a wire localization so the surgeon would know exactly where to operate.

The total cost of all those procedures was just under $16,000.

Fortunately, I have health insurance and ended up paying only $800. I say only because it’s a far cry from $16,000, but it’s still a chunk of change and I don’t happen to have a lot of disposable income. (Let me add that I’m extremely grateful the DCIS was caught early and treated.)

Difficulty paying medical bills

I was able to pay my medical bills, but an estimated one in three people in the United States run into trouble.

It can be just as difficult for people who are insured as it is for those who aren’t.

Here’s why:

- high deductibles

- unaffordable or difficult to afford premiums

- out-of-pocket expenses

Whether you have health insurance or not, do you worry about the cost of your health care? If you do (or even if you don’t) have you ever considered asking your doctor or any other healthcare provider how much an office visit or a test or a procedure will cost?

When I was going through my experience, at no point along the way did it even occur to me to ask how much something would cost. At the time, all that mattered to me was where I would have things done and by whom.

But if I had asked, the law says I should expect an answer. Maine lawmakers passed two cost transparency bills last year.

LD 1642 requires health care practitioners and facilities to make the prices of their most frequently provided health care services and procedures available to all patients.

LD 1760 requires hospitals and ambulatory surgical centers to provide the average charge per procedure to any patient who asks. They must also give uninsured patients a total price estimate for their care as well as information about the hospital’s charity care policy.

In retrospect, I wish I had spoken up.

Why ask about cost?

Think about it. We ask in other areas of our lives. Something needs fixing and we want a detailed estimate. We need to buy a new appliance and we compare makes, models and prices. We go out to eat and make choices from a menu of options.

So why don’t we ask in the doctor’s office? Primarily, because we’re simply not used to asking says Poppy Arford, who recently gave a patient perspective on “Price & Cost Transparency” at the Maine Quality Counts Conference.

“We need to be asking because we need to understand that we’re actually paying the bill,” says Poppy.

“We’re paying through our health care premiums — nobody at the insurance company is taking money out of their pocketbook to pay for our healthcare. Every single bill is paid through health care premiums, through the money they get from you or me. We’re also paying through our tax dollars or through reductions in other needed health and welfare services. [And meanwhile,] premiums are going up, taxes are going up and services that we’re accustomed to are being cut or reduced or not happening at all.”

Poppy is passionate about getting people to think about what they’re paying and to speak up. Asking how much may not have an immediate impact on the high cost of health care in the United States, but it’s a way for individual patients to begin their own conversations and take a more active role in their care.

“Can you imagine,” asks Poppy, “if we were doing this across the country? Things would change.”

How to ask

If you’re not sure how to start the conversation, you can cut right to the chase and ask “How much will this cost?”

If you don’t get a satisfactory answer, ask to speak to someone who can give you one.

Here’s a scenario from Poppy in which a doctor has ordered an in-house test and the patient knows it could be done more cheaply at another facility.

“You could say to the doctor,” says Poppy, “I’m aware of the fact that this place down the street offers the same exact test for $200 less. I would like you to either match their price or to write me out and order to go have the test done down there.”

Now that’s a simplistic example and it begs several questions, but she’s just trying to put the notion of looking at cost into our heads.

“It’s got to be ok,” she says, “especially for people who are struggling and probably putting off necessary procedures or treatments, to be able to ask about cost and to say ‘I’m not sure I can afford this or agree to this treatment until I understand what it’s going to cost.’ The system has got to deal with that. People have got to be able to tell the truth.”

The extreme consequences for people who are struggling are that they either go bankrupt trying to pay their medical bills or they don’t get the medical care they need.

What else should we ask?

Dr. Dora Anne Mills, Vice President for Clinical Affairs at University of New England and former head of the Maine CDC, shared an article on her Facebook page this week that gives us more reasons to ask questions about our medical care. The article, which appeared in The New Yorker, was written by Dr. Atul Gawande about the waste (not just in dollars, but in lives) caused by over-testing and too many procedures.

This is a quote from Dr. Gawande’s article (who, by the way, was the keynote speaker at the Maine Quality Counts conference.)

“Virtually every family in the country, the research indicates, has been subject to overtesting and overtreatment in one form or another. The costs appear to take thousands of dollars out of the paychecks of every household each year. Researchers have come to refer to financial as well as physical “toxicities” of inappropriate care—including reduced spending on food, clothing, education, and shelter. Millions of people are receiving drugs that aren’t helping them, operations that aren’t going to make them better, and scans and tests that do nothing beneficial for them, and often cause harm.”

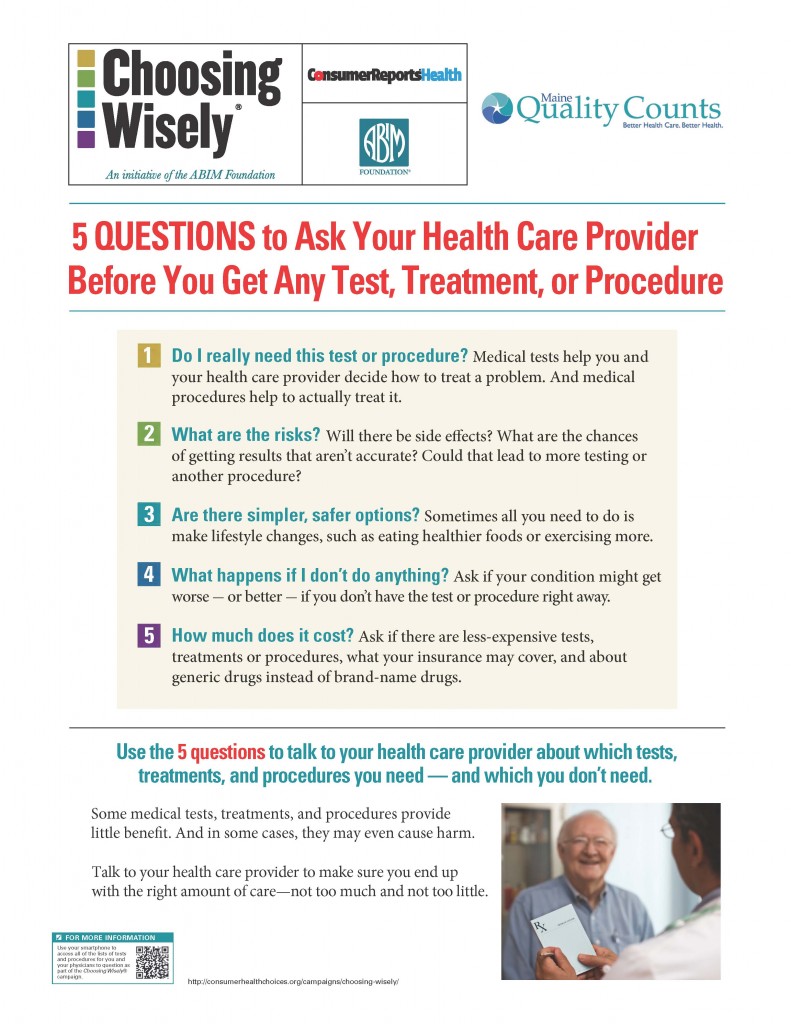

In other words, not only should we be asking how much is this going to cost, we should also ask why do I need this test, this procedure, this treatment? How will it help me? How might it harm me?

I might not have asked about cost during my health scare, but I did question treatment options. The result was that I opted not to have radiation therapy treatments. I won’t go into specifics, but I discussed it thoroughly with my surgeon and also got a second and third opinion and decided that the risks of radiation outweighed the benefits at this stage of the game. If I hadn’t asked, I’m quite certain I would have automatically been referred to radiation therapy.

Asking questions about procedures and treatments (and prices) when you’re scared about your diagnosis takes a lot of energy and focus. It doesn’t matter what you’re up against – it could be back surgery, a joint replacement, a heart procedure, anything at all. What I quickly learned is that you’ve got to put your emotions aside momentarily and figure out what questions you should be asking.

The Choosing Wisely in Maine campaign recommends these five (including how much does it cost?)

Online resources

On the subject of cost, in addition to asking your healthcare provider how much, there are several online resources that may also be useful.

Harvard Pilgrim – Now iKnow (for members)

Aetna – Member Payment Estimator (for members)

Anthem BCBS – Estimate your Costs (for members)

What about you?

Have you ever asked how much a medical test or procedure would cost? What was the response? Do you agree that it’s important to know the cost of your medical care up front?

if you ask about prices, expect a bigger bill on something unnecessary and dumb… Q-tip ear check-up… Q-tips = $200?

Went to dermatologist to check on my acne. Said it would go away in a few months but asked if I wanted an injection to speed up the process. Didn’t mention anything about costs. Month later, i get a bill for $150! I would not have accepted the treatment knowing that. Don’t know why prices was not given beforehand like when i take my car in for repair.